China’s drift towards a Zero-Speech policy is not sustainable

China’s censorship regime, while understandable in a sense, is nonetheless a failure

View from China with an Austrian School of Economics Perspective

This article is an expanded excerpt from our previous article entitled “Global Race to the Bottom”.

The Chinese censorship regime has two parts: the censorship of foreign content, meaning principally the foreign Internet, and the censorship of domestic content.

Without necessarily justifying this policy, it’s important to realize that the primary goal of China’s censorship of foreign platforms and sites is not to cut off Chinese from foreign sources of information. Rather its goal is to ensure that China develops and maintains its own domestic ‘Intranet’ which is not dependent on foreign systems. For one thing, China’s government wishes to maintain its own data sovereignty, and this means not depending on foreign social networks such as Facebook or Twitter, on browsers like Google, or on video sharing platforms such as Youtube.

China also blocks most Google services. Google employs extensive user tracking services, gathering detailed information on users through its various services and its Android cellphone platform. China’s blocking of Google limits the degree to which these tracking tools can reach into China. China does use a modified version of Google’s Android operating system on many mobile phones; however, users do not have a Google ID and do not have access to Google Play.

Russian platforms such as VK or Yandex are accessible, but are not very heavily used.

In terms of content screening, the Chinese strategy is to generally limit access to Western content, instead of attempting to screen it to decide what constitutes ‘fake news’ and what does not. Given the enormous volume of questionable ‘news’ about China spread through Western media and social networks, at a minimum this has to be considered understandable.

If a small percentage of the population occasionally accesses Western platforms and sources, that does not conflict with the above goal.

On the domestic front by contrast, the government does engage in content screening. All websites and applications need to be registered. For publicly available content (though normally not for 1:1 messaging), these are responsible to comply with the government’s latest censorship guidelines. The big problem with this is that these ‘guidelines’ are constantly changing and not officially published anywhere. This obviously leads to self-censorship, which restricts even further what can be published.

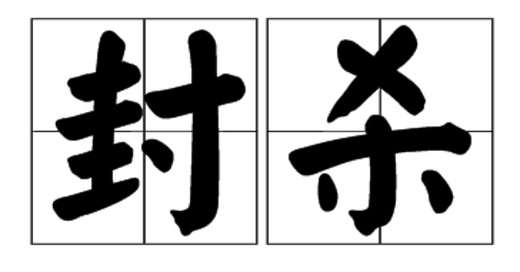

If government censors don’t like some piece of content, they will typically contact the registered admin for the relevant website and ask him to take this piece down. The term typically used for this is ‘bèi fēngshā le’ (被封杀了). One gets the impression that the censors themselves are often not sure what is banned and what is not. When in doubt they tend to err on the side of caution, i.e. censor it. Social networks do risk being fined for not being (in the government’s opinion) sufficiently vigilant in their self-censorship; however, for most sites as long as the censors aren’t calling up several times a day, this is also normally not a problem and does not lead to repercussions.

For individual users such as those sharing content via Wechat Moments, the typical punishment for frequently sharing unbeloved content is comparable to Facebook jail – albeit usually lasting only 1-2 weeks. Those found guilty of serially sharing unbeloved content are in theory subject to long-term ‘cancellation’, but this is in reality quite rare. We did however cover several examples of this in our January 2022 review of China’s 2021 cancel culture:

It’s worth noting that ‘cancellation’ in China is far rarer than the kind of permanent cancellation until recently practiced in the West on Twitter.

In its early days, the censorship was fairly light and not particularly burdensome. That has however changed in recent years. During the past year, sometimes it has been hard to escape the impression that it amounts to a “zero-speech” policy with regard to public expression of opinion.

This policy is primarily characterized by a very long list of words and terms banned from use in chat groups and on public platforms, including the name of the big kahuna himself, as well as his various nicknames. Naming the imaginary pandemic is also forbidden. Instead, the “masking problem” (“口罩问题”) is used as a euphemism. Moreover, as mentioned above, not only is the use of all these terms banned, but none of this is ever officially communicated. Apparently you are just supposed to know. For Chinese speakers, former CCTV anchorman Wang Zhian did a handy episode explaining all of this. Only state-run media outlets are allowed to use these terms. How is a modern industrial society supposed to be able to function with such extreme low tolerance for public discussion of any topic upon which the government has expressed an opinion?

One result has been that more and more news ends up getting transferred via 1:1 messaging. The government can (and does) occasionally demand that platforms such as Wechat censor such messages, as well, but such restrictions are notoriously easy to circumvent. The other effect is to shift ever higher percentages of the public debate to foreign platforms such as Youtube or Twitter.

While censorship of opinions in the West by Western “Big Tech” companies is increasingly severe, their censorship policies vis-à-vis Chinese language content is relatively light, with news programs such as the one by Wang Zhian quickly garnering hundreds of thousands of viewers on Youtube.

If trends towards ever harsher censorship continue in the West, perhaps one day we may see the inverse phenomenon, with dissident Western social media platforms forced to resort to Hong Kong-based platforms to avoid censorship at home.

Yet even on domestic platforms, the government’s censorship engine is fairly ineffective. Billions of private interactions every day are hard to monitor. By the time the censors allocate a high priority to censoring a particular piece of information or video, usually millions have already seen it. Since China still lacks the mythical social credit system the Western media have been promoting for years, there very little downside for those sharing information.

Our forensic analysis of the social credit system myth:

To our knowledge, no government leader has ever even attempted to deliver a justification for its “Zero-Speech” policy. Or for its Zero-Covid policy, for that matter. Policies need not only to be understandable, but also to be explained to those expected to live with them. That has not happened.

China had strict but local lockdowns, while Western countries had nationwide but softer lockdowns. If you express this in person-impact-hours, Western countries locked down infinitely harder.

You could do a similar calculation for free speech. You say the Chinese can express their opinions by avoiding certain words and not mentioning their leader. In the West, social media enforces a very narrow narrative. Social media does not allow euphemisms like "masking problem": when many people use it, it is banned. You cannot voice displeasure against woke viewpoints. I would not be surprised if Chinese people are more able to voice what they feel than European people.

pooh! yea i said it!