View from China with an Austrian School of Economics Perspective

In our next post, Man Tianmai (漫天霾) reflects on what China lost in 2021 – too many goodbyes, as he puts it. This post was originally written to provide context to Western readers of that essay. Here we ask the question: what got cancelled and what did not? It was originally entitled ‘Lamenting China’s 2021 Cancel Culture’.

China’s new cancel culture bears some distinct resemblances to its Western counterpart: It is authoritarian and increasingly intolerant of everything deemed politically incorrect – even if that “incorrectness” lies far in the past. What is politically incorrect in China is of course different: there are still only two genders in China, for instance; there is no organized campaign to change or abolish traditional cultural values, and no-one is being banned from society due to personal health choices. Moreover, the Chinese cancellation regime seems to be much more top heavy than the one enforced by Facebook and Twitter. Those who get cancelled tend to be prominent. But when a ban comes (遭封杀了), as it has come to so many in the United States and Europe, it tends to be complete. Social media, commercial platforms and social status – all can disappear overnight, with not only their public presence but even their past publications and videos gone. All down the memory hole.

It is not only these individuals who lose out. The entire society is impoverished by their loss.

However, this is not the only kind of cancellation which is taking place. There are other subtler kinds, as well, cancellations which involve society and culture as a whole. The world as a whole has moved from a culture of open debate to one where only certain opinions are tolerated and all others are castigated, and in this, China is absolutely no different. Just as travel has been cancelled and constricted, opinions have, as well.

At the same time, bit by bit China is being transformed from a country with a decentralized minimalist government nurturing a culture of entrepreneurship, competition and private sector-driven innovation into a country with an increasingly centralized big government propagating the idea that better governance is the cure to all ills.

This is the actual focus of Man’s essay. It is also the focus of this essay, albeit with a somewhat broader perspective. Part of that broader perspective is the important reminder that not yet all is lost, and the good fight is still being fought.

Thus far, Chinese big government has a track record of hardly more than a decade. Notoriously inefficient and often technically incompetent1, it is anything but omnipotent, and memories of the bankruptcy of Mao-era socialism are still intact. There is still effectively no welfare, the regulatory state is still far slimmer than the stifling straightjacket which passes for normal in much of the West, and despite some dark clouds on the horizon, respect for property rights and personal financial freedom remains (mostly) intact2. Moreover, civil society (民间力量) remains strong, and when big government egregiously fails, the private sector continues to remind people of the superior results it can deliver.

That reality does not however change the fact that there were a number of goodbyes which bear remembering.

Goodbyes to key opinion leaders

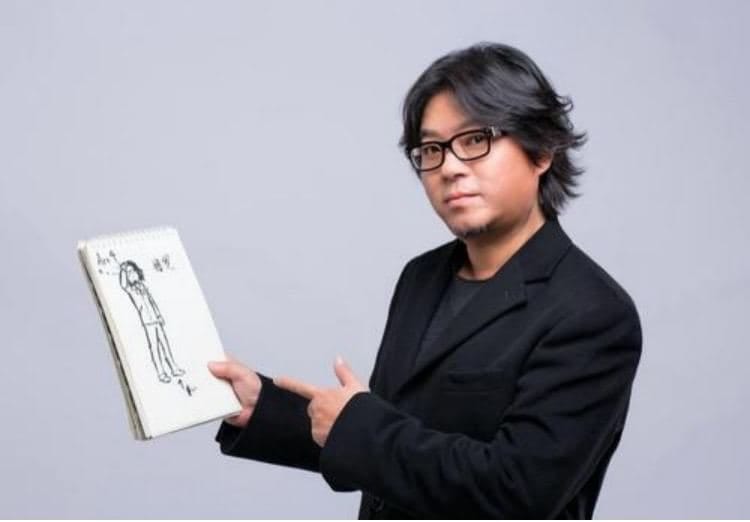

Before we go on to the wider societal issues, just to provide a rough idea, here are a few examples of the kinds of individuals who ended up getting themselves cancelled.

They include public intellectuals such as Gao Xiaosong (高晓松) or Yuan Tengfei (袁腾飞), celebrities from the entertainment industry such as actress Zhao Wei (赵薇), but also increasingly many prominent Chinese entrepreneurs with a social media presence such as Wei Ya (薇娅).

We published an entire post on the Wei Ya case, and it forms a key part of Man Tianmai’s article, as well.

To be clear, this does not mean that these people were ‘disappeared’, as adherents of the ‘China dystopia’ narrative might imagine. Just as in the West, it’s a virtual jail, not a physical one. On the ground this means that victims are blocked from a role as a public figure, be it on social media, on the screen or on the domestic Internet.

Yuan Tengfei became famous for his entertaining and insightful lectures on Chinese history, some of which were highly critical of Mao Zedong and complimentary towards Mao’s rival Jiang Jieshi (Chiang Kaishek). When he first rose to fame 13+ years ago, the government was still highly tolerant of such viewpoints, permitting frank discussion of most historical events in the past 100 years. Yuan called Mao one of the "three great despots" of the 20th century. Since then however, the red lines have completely shifted3. Yuan Tengfei was cancelled on November 25, 2019.

Gao Xiaosong, one of China’s best known public intellectuals with a following of 44.6 million on Weibo, was likely also banned due to his frank and balanced discussions of historical topics. Weibo is China’s leading blogging platform and has long been a preferred target for the censors. To give an idea of the breadth and depth of Gao’s following, his insightful and erudite talk shows on history and culture regularly enjoyed 6 million+ views as soon as they became available online, with one of his “Morning Call” episodes on the Youku platform exceeding 40 million views. He is also a composer, novelist, director and film producer, with both top-10 hits and films to his credit. In April 2014 iQiyi outbid Youku, agreeing to pay Gao the equivalent of $16 million to produce a series of talk shows for their platform. In July 2015 Gao Xiaosong was named the chairman of Alibaba’s AliMusic group, which acquired Youku in November of the same year. This brought Gao back to Youku, where he continued to produce regular talk shows. In his role at AliMusic, he had a very close relationship with Jack Ma, and was also appointed as the head of Alibaba’s Entertainment Strategy Committee. He was cancelled in September 2021 and all of his content taken offline4.

The actress and top-10 celebrity Zhao Wei was also axed around the same time, for unknown reasons.

Goodbye to regional competition?

Professor Steven Cheung (张五常), a legend among Chinese economists, once noted that one of China’s most valuable assets in its struggle to build up a world-class competitive economy was its extensive regional competition – what he called 县域竞争, literally county by county competition. Provinces, counties, cities, special economic zones and even towns were allowed and encouraged to offer a unique set of incentives and conditions to both residents and businesses. Much policy making was decentralized, with a range of government entities competing to offer the most attractive possible package of conditions to both residents and businesses. Both people and businesses went where the conditions were best. Competition works, and this competition in combination with minimalist government ultimately led to a level of prosperity unprecedented in Chinese history.

With the exception of a one-time event in 20135, probably one of the main reasons for the success of this regional competition has been a relatively high level of long-term policy stability in most provinces. This de facto continuity of policies on a provincial level is in fact arguably one of the most unique aspects of China’s political system. To an extent, the efficacy of this long-term approach might be said to reflect the logic which Hans-Hermann Hoppe elucidated in his 2001 classic “Democracy: The God That Failed.” Every now and then the central government’s HR department will send in people from outside, but the bulk of officials remain locals, and for the most part the incoming officials seem to be reluctant to rock the boat by demanding too many changes.

So for example, Shanghai has long been known to be a bastion of right-wing thinking, with a strong preference for a night watchman approach to business and a reputation for efficiency. This was Shanghai’s reputation in 1990 and it is still Shanghai’s reputation today6. Xi’an (Shaanxi province) by contrast has the opposite reputation.

In this respect, there are indeed some real parallels between China’s economic success and the relative success of some American states. Just as in China, US states also offer different packages to residents and business, with the result that some states have prospered while others have literally run their economies into the ground. The value of this policy competition has been especially apparent in the past two years, with radically different policies leading to radically different results. Some policies have worked, while others failed spectacularly.

“May the best man win,” as it were.

In 2020, to a large extent this was not permitted to happen in China.

Control of Covid-19 was declared to be more important than all other considerations, with no public consideration of costs permitted. At least in terms of the policy itself, a uniform size and uniform shoe shape was declared to suit all provinces. While this shoe was quite different from the shoes forced on Western countries – for example because people who test positive but lack symptoms are not considered to be cases – that did not make it any less constricting.

“To a large extent” means however with exceptions, and the exception in this case was that the interpretation and implementation of these policies was left to individual provinces. This remaining flexibility did lead to somewhat different results. Though these differences were not as large as, say, those between the red and the blue states in the United States, they were however significant.

In many provinces for example, if you live in a zone where there is an asymptomatic person who has tested positive, you risk landing on the list of “potentially infected” people. This can affect your ability to travel to other cities. In Shanghai by contrast, the Covid-19 control team does not do this.

In per capita terms, Shanghai also has one of the largest contact tracing teams in all of China (3000+), and perhaps thanks to this, Shanghai has never had a Covid-19 case outbreak where the source of the outbreak could not be pinpointed. The Xi’an contact tracing team by comparison allegedly only had around 300 people for a city with a population half the size of Shanghai, and in the case of the recent outbreak, it failed to identify the source. This failure led to a city-wide lockdown under which workers deemed non-essential were prohibited from leaving their housing subdivisions.

These events left Chinese feeling that something was amiss, and yet, as Man puts it, faith in the state rarely seemed to waver for long. On the contrary, the epidemic reinforced their "religious identity" in every way. The government pointed to the chaos underway in the West, patted itself on the back for its allegedly successful “zero Covid” strategy, and those not directly affected by the resulting chaos for the most part approved.

As we pointed out in our previous background info post on China’s Covid-19 regime, it is true that after April 2020 China for the most part avoided the kind of sweeping measures which disrupted life across much of the West. Yet as discussed in that article, nonetheless millions of people and businesses were impacted by these centrally mandated policies, and for them, the consequences were no less devastating. When one policy is mandated to fit all, is it not inevitable that absurd decisions are made and many people fall between the cracks?

Moreover, no amount of burnt sacrifices can compensate for a bankrupt policy, and this is unfortunately a common result of centralized decision-making. It is hard to deny that the lockdown imposed on 13 million people in Xi’an last month is ample proof of this.

Goodbye to small government?

When Xi Jinping came to power in November 2012, the infrastructure gap between China’s top metropolises and the rest of the country was still enormous. Many motorways had been built, but rural exits often led to dirt roads. Where the roads were paved, enormous potholes were the norm, not the exception. Even driving through second tier cities such as Tianjin at times resembled negotiating an obstacle course. And while the standard of living for Chinese in rural areas and small cities had also improved dramatically since the demise of socialism in 1980, standards for housing, medical care and schooling still lagged far behind those in China’s cities.

Xi Jinping vowed to change all this, both by realigning the government’s investment priorities, and by increasing government efficiency. On the ground, that translated into:

a massive buildout and improvement of road infrastructure throughout China, including remote areas

a massive buildout of airports, high speed train infrastructure and subway systems

restrictions on the use of government funds to build fancy new administrative offices

hard crackdowns on government corruption, thereby increasing the effectiveness of invested funds

targeted poverty alleviation plans, some of which involved coercing people into abandoning remote settlements

targeted development plans for remote areas such as Xinjiang and Tibet

Some funds were no doubt wasted on prestige projects, such as the new Beijing airport in Daxing. Yet it cannot be denied that these efforts did yield some very visible positive results. Just to cite the most obvious: China now has over 160,000 kilometers of motorways plus 40,000 kilometers of high-speed rail lines; the total size of these two networks surpasses the rest of the world combined. And for the most part, nowadays the roads are indeed excellent almost everywhere, even in very remote areas. So much so that sometimes it’s hard to avoid the impression that China’s government now sees its primary role to be that of a road builder.

Be that as it may, these investments in infrastructure did have real long-term benefits, both concretely in terms of an exponential rise in property values near all the new train and subway stations, and intangibly in terms of decreased travel times and increased overall efficiency in the economy.

At the same time, the previously widespread cynicism about local government receded noticeably, especially in rural areas. Central government has long enjoyed a far higher degree of popularity than local government, and this was maintained, with China’s central government (according to the Edelman Trust Barometer) continuing to enjoy the highest level of popularity of any government in the world throughout the previous decade7.

Yet, at what price? As we will see, this burst of government spending did not come for free. On the contrary, it has some quite insidious side effects.

On February 25, 2021, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced that poverty had been conquered. With that goal accomplished – at least in theory – the focus has shifted to a somewhat murkier goal: “common prosperity”. This is the official translation for “共同富裕” in Chinese, a goal which was announced in August of 2021 and is often interpreted as a call to redistribute wealth. This theme was not without some resonance in the wider public. One of the main reasons for this resonance is to be found in the side effects of the money printing mentioned above.

As discussed in our previous background info post on Society & Quality of Life, it is true that - for the most part - optimism about the future continues to characterize Chinese society. Nonetheless, there is a shadow over that general optimism, a shadow that expresses itself in an increasingly apparent generation gap.

Whereas older generations retain a memory of poverty and the abject failure of socialism, young people lack all such experience. For these later born generations who have never known want, the idea of “sharing the wealth” has an appeal it can never have to earlier generations.

Moreover, there is one other crucial difference between the generations: For the most part, the “pre-1990” generation saw their personal wealth explode over the course of their lifetimes, whereas many members of the post-1990 (“90后”) generation experienced nothing of the sort. Instead, many of these are now paying the price for 14 years of rabid money printing.

Between 1995 and 2007, total Chinese government spending grew slowly from 11% to 18% of GDP. The books were balanced and there was virtually no deficit8. Most of China’s urban housing was privatized in the middle of this period, between 1998 and 2003. This privatization was done in a very democratic way, with most long-term residents of China’s cities obtaining one or more apartments, thus creating a basis for future wealth. These properties grew steadily in value; yet initially they were still at levels attainable by newcomers moving up the economic ladder.

After 2008 however, something changed. Keynesians took over monetary policy in Beijing, just as they did in most of the industrialized world, and began expanding the money supply by 11% per year on average. Government spending as a percentage of GDP rose each year, and the government began running deficits. Between 2008 and 2022, all that newly printed money had to go somewhere, and in China most of it went into residential real estate, principally in the major metropolitan areas. With tens of millions of apartments now worth $1 million or more, the people who in 2008 had property in the 20 or so top cities did spectacularly well, while the newcomers and renters saw their hopes of property ownership dwindle with each passing year9.

At a minimum, it has to be acknowledged that this leads to legitimate frustration. It is a serious problem caused by a dishonest monetary policy. Yet instead of addressing the root of the problem, as Ludwig von Mises predicted in his Critique of Interventionism (1929), the Chinese government opted for yet more interventions to address the issues they themselves created in the first place, mostly involving various restrictions on purchase eligibility and restrictions on bank lending.

Given the government’s refusal to address the underlying cause, it can hardly be surprising that none of these had any long-term impact.

As long as this problem remains unresolved, the seeds of discontent planted will continue to bear poisonous fruits. As we shall see, these fruits are already quite visible.

Goodbye to foreign capital? To an extent yes, but only to an extent.

Starting during the Obama era, the US began to issue policies encouraging US companies to disengage from China, for example by offering subsidies to companies willing to move production out of China. These policies met with little enthusiasm. New anti-China policies followed during the Trump era. Tariffs of 10-25% on Chinese products were introduced to encourage companies to leave China. At the same time, Chinese companies active in the US were faced with increased harassment, with regard to both their products and financial structures if listed on the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE).

Partly as a result of these US government actions against US-listed Chinese companies, starting in June 2021 the Chinese government adopted an open policy of encouraging US-listed companies to move their primary listing from the US to Hong Kong. The trigger for this may have been the Didi case. In the summer of 2021 Didi, China’s Uber equivalent, listed briefly on the NYSE without first obtaining a green light from China’ Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC / 证监会)10. It was forced to delist shortly thereafter, and as an additional punishment, Chinese app stores were forced to remove Didi’s app from their listings. Six months later, Didi’s app still remains delisted.

This seems to be part of a larger campaign to reduce the influence of Western capital over major Chinese corporations, a policy which not only affects foreign stock exchange listings, but also effectively precludes any large direct investments in Chinese companies by investment and private equity funds. The CSRC’s blockage of Blackstone’s $3b June 2021 offer to purchase majority control over Soho Real Estate was a prominent demonstration of this policy. Shortly thereafter, the government punished Soho for this attempt by fining them 790 million yuan (approx. $125 million) for alleged tax code infractions.

That said, it should be noted that these policy changes do not (yet) seem to have had significant impact on foreign direct investment (FDI) into China. Thanks to China’s unique status as the only normally functioning industrialized country, these rebounded strongly in 2020, returning China + HK to the top of the FDI league tables.

Goodbyes to some of China’s star entrepreneurs

For a long time, getting on the Forbes Top 10 rich list was something to be proud of. However, since 2008 at the latest, it has gone from being a source of pride to a serious danger11. Almost of the people on the list were company CEOs, and government tax auditors started investigating them one by one, looking for misdeeds.

2020 saw the persecution of a number of actors and actresses for tax transgressions. In 2021 this was followed by the persecution of a number of China’s most admired entrepreneurs.

In reality, the increasing wealth disparity in society has nothing to do with any of these; yet as Man points out in his essay, sadly many in the public applauded these actions.

At times, this has come across as a centrally managed witch hunt against China’s most innovative privately owned Chinese companies, some of which were literally tragic. A few victims such as Jack Ma are fairly well known outside China, but most remain comparatively unknown. When Jack Ma was forced out of his position as president of China’s top private company Alibaba, many of his staff literally cried. He meant that much to them.

At the same time, Alibaba was fined the equivalent of $2.8 billion for alleged monopolistic practices12. This was after the government ruined the planned IPO for Ant Financial (蚂蚁金福, the operator of Alipay) in October 2020. It would probably have been the biggest IPO of all time, but the government used a long list of new regulations to sabotage it. At the time Ma had some choice words for the state of Chinese financial regulation which apparently they did not take kindly13.

Some of these witch hunt victims we covered in the introductory piece to this series, entitled “Why Austrian China”. As mentioned previously, we also covered the sad Wei Ya cancellation story referred to by Man in his essay in an article devoted to her14. A few other victims of cynical public shaming Man mentions are the delivery service Meituan, which was pilloried for not paying social security payments for its gig workers, as well as Yu Minhong, the CEO of New Oriental, for trying to find alternative work for his employees after the government destroyed his education business. There have of course also been others. It is a shameful list.

In 2021, Meituan was also fined $580 million for alleged monopolistic practices. Perhaps not coincidentally, both Alibaba and Meituan are listed on the New York Stock Exchange.

Goodbye to private property rights and the equal rule of law?

Respect for the rule of law and respect for property rights are the two foundations on which China’s current prosperity rests.

In a law-based society, respect for the rule of law means that the rules of the game are public, that the justice system judges according to these laws, and that the executive branch of the government can reliably be counted on to enforce the rulings of the judicial branch15.

Respect for property rights, on the other hand, is even more crucial than this. It is an irreplaceable prerequisite for the long term prosperity of human society, and since the launch of Deng Xiaoping’s reform process (改革开放) in 1980, loyalty to this principle has for the most part been ironclad. Unlike for example a number of American states which use ‘civil forfeiture’ to confiscate property without due process, in today’s China, property rights may only be abrogated with due process establishing a debt. Police may for example ask a bank to freeze an account, but they cannot maintain this freeze indefinitely or simply confiscate the funds.

However, there is a related third principle. That is the idea that laws must be equally applicable to all. They cannot be applied arbitrarily. This third principle is not only essential to meaningfully implement the first two; it is also a key requisite for civilized society. One of China’s greatest accomplishments of the past 20 years has been an increasingly widespread respect for this principle both among the people and within the government.

Arbitrary enforcement of laws and regulations with the goal of coercing compliance with the wishes of officials is in direct contravention of this third principle. Yet on its own the occasional existence of abuse is something which the system can survive. What is crucial is not the existence of abuse, but rather the attitude of the executive branch. The key question: Is this kind of behavior considered to be acceptable or not? If it IS deemed acceptable, i.e. if abuse (1) becomes systematic, and (2) is not punished and denounced16, in the end it also undermines the first two principles – the rule of law and respect for property rights.

In 2021 there were a number of cases where large companies were effectively punished using such tools. Call it tax evasion, monopolistic behavior or environmental crimes, if the fines for these alleged crimes are in reality the result of the government’s wish to punish a company or force it to follow its directives, this makes the idea of rule of law into a farce17.

Moreover, if government officials can and do arbitrarily punish nominally private companies for a failure to follow their orders, in reality this is an attack on the property rights of their owners. These companies become something less than truly private. This degradation of status inevitably risks undermining the value of those once golden goose eggs.

To be clear, at this point we are talking here specifically about large companies. This perversion of law does not seem to have yet trickled down to the treatment of small and medium-sized ones. And the insidious effects of such external coercion are still far less devastating than outright government ownership. Yet once the principle is established, the danger is that this barbaric principle eventually permeates the entire society.

Goodbye to private sector dominance over the economy?

The question is, has this abuse become systematic? And if so, how deep will the damage go? While it is still probably too early to answer these questions, it cannot be denied that the central government has made no move to denounce and punish the officials responsible for these egregious cases, perhaps because in many cases they in fact reflect decisions made at the very top. Eventually, this will inevitably lead people to suspect that this might in fact be the “new normal.”

Nonetheless, as insidious and destructive as arbitrary external coercion can be, it should not be forgotten that in terms of efficiency, productivity and employment, the effects of outright government ownership are far worse. At least for China, the numbers are absolutely unequivocal on this point. Just to cite a few statistics, the Chinese private sector generates ~93% of all new patent applications, ~85% of new investment in manufacturing and, on the net, 100% of all new jobs18.

These are contributions which state-owned enterprises cannot possibly replace. As shown in the following analysis published by the World Bank in 2019, approximately 75% of China’s economy remains outside of the government’s direct control19, and there is no sign of a trend reversal.

Despite the disturbing trends at the top of the economic pyramid, as of January 2022, China’s privately owned businesses for the most part remain highly competitive and – as a result – highly innovative. Low levels of government regulation mean that large companies cannot rely on government to protect them from up and coming nimbler competitors.

And even where government does attempt to interfere, such as in social media, still there is a limit to how much it can sabotage using various forms of external coercion. Realistically we know from experience that government central planners cannot manage high levels of complexity. The more they try to plan, the more disastrous the results are. Nonetheless, clearly this does not stop them from trying.

While many of China’s largest companies in terms of market capitalization continue to be state-owned, the overall importance of these SOEs to the economy as a whole should not be overestimated. “China is home to 109 corporations listed on the Fortune Global 500 - but only 15% of those are privately owned,” notes for example one article from May 201920. While such claims may be technically accurate, the top two are privately owned, and more importantly, market capitalization is not reflective of the broader economy. In terms of sales, exports, employment and investment, the share of the state-owned behemoths is small. Most industries, including key ones such as payment processing and the IT/Internet industry, are completely controlled by privately owned companies.

Both Western socialists and much of the “conservative right” often seem to agree that China’s success is built on the back of sublimely inspired central planning plus (in the case of many right wing pundits) “slave labor.” Yet if economic success really were that simple, why did the Soviet Union and Maoist China do such a miserable job of outperforming the West? Strangely this rather obvious question never seems to get asked.

The numbers tell a different story. In reality, China’s greatest asset is its highly competitive private sector, its golden goose that has produced an endless series of golden eggs and enabled it to become the world’s leading trading nation. Would it not be foolish to abandon this?

What is the alternative?

A glance at the far less competitive West offers some useful insight what an alternative might look like.

In the West there is no adversarial relationship at all between big business and big government. On the contrary. In 2020, most of these businesses were declared to be essential, while many smaller companies were ordered to shut down. In the end, countless small and medium-sized businesses closed their doors forever, while sales and stock values for the top corporations soared.

Can all this chumminess in the West be simply an accident? A lucky quirk of fate? This seems unlikely. No, there is likely a very good reason for this, and though it is not a topic the Western financial press writes about, publicly available financial data provides some big clues: In the USA, Fortune 500 companies represent approximately two-thirds of the U.S. GDP with $13.7 trillion in revenues and $1.1 trillion in profits21. Of these, the interlocking investment funds of Blackrock and Vanguard22 have controlling stakes in at least 80% if not 90%23. This means that at least 50-60% of the US economy is effectively controlled by Blackrock’s Larry Fink, while the non-Blackrock part of the economy is only 40-50%. The 80%+ of Fortune 500 companies controlled by Blackrock/Vanguard include companies as diverse as Facebook, Microsoft, Walmart, Amazon or McKesson.

When considering such numbers, it should be noted that some Fortune 500 companies have special share classes with enhanced voting rights. Two prominent examples of this are Meta (Facebook) and Alphabet (Google), both of which have special share classes with more voting rights controlled by the founders. As a case in point, while Blackrock/Vanguard through its various funds and sub-funds controls at least 29% of Meta’s common shares, Mark Zuckerberg with control of only ~10% of total shares still controls 57.7% of voting power.

Does that mean that Mark Zuckerberg can ignore Larry Fink’s opinions in his decision making? Probably not. After all, even aside from its influence over government, Blackrock still has the ability to destroy Meta’s stock price at any moment.

As a point of comparison, Blackrock controls at least 28% of the shares of Facebook’s “competitor” Twitter. At the end of 2019, former CEO Jack Dorsey owned 2.3%. In its proxy statements submitted to the SEC, Twitter does not mention any special share classes.

Blackrock/Vanguard also controls at least 27.3% of Pfizer and 25.3% of Moderna, both huge beneficiaries of the printing press in 2021. Though not impossible, it is very difficult to outvote a shareholder with a 25% interest, especially one with the kind of influence Blackrock has.

As Fink himself made clear in his 2017 Letter to CEOs, Blackrock is not a passive investor, and when Blackrock issues political mandates (such as the vaccine mandate issued in mid-2021, or mandates to sanction products from Xinjiang), for the most part his CEOs have no choice but to follow suit, regardless of the impact on their bottom line.

Are these Blackrock companies comparable to China’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs)? Perhaps not in all senses, but in many. For Western readers wishing to understand the key differences between China’s economy and that of the West, this point is absolutely crucial. Both are by definition non-competitive and subject to all the ills of central planning. Just like China’s SOEs, Blackrock has de facto direct access to the central bank’s money printing machine and their top staff regularly rotate in and out of government regulatory agencies24. For both Blackrock and China’s state owned enterprises, political considerations are the bottom line, not economic ones. In many US industries, literally every major company is controlled by Blackrock, which necessarily limits the degree of real competition.

While there are many similarities, there is one huge difference between China’s SOEs and the Western Blackrock companies. Chinese SOEs make up only ~25% of the Chinese economy, a number which pales in comparison to the 50-60%+ share Blackrock enjoys in the US25. In the US and to a large extent in Europe – though less well documented there – Blackrock has become the central planning establishment. In 2020-2021 the reality of this central planning revealed itself in countless ways, but perhaps the most obvious one was in Blackrock’s ruthless exploitation of the once flourishing social networks it controls. Facebook and Twitter’s long-term market dominance and commercial success were sacrificed on the altar of Blackrock’s political agenda. Control and manipulation of public opinion are key components of any power structure, and events of the past two years have proven that Blackrock (or the people who control Blackrock) have both the ability and the willingness to use this control.

This fact may explain the phenomenon we noted at the outset of this essay, namely that China’s cancel culture seems to be far “top-heavier” than its Western counterpart. In light of the above data, it is not too hard to guess why this might be. The key insight is that the amount of influence which can be effectively exercised via regulatory and punitive measures is far more limited than what can be accomplished with direct control. The limiting factor is the willingness and ability of government officials to do actual work.

Chinese central planners by contrast have no such direct influence over the most of the economy – thus far. That at least some powerful people in the Chinese government would like to change this, is clear. But will they succeed? Only time will tell.

With that in mind, for a personal view read on to Part II here.

A good illustration of this is the consistent inability of most Chinese government entities to create and run reliably functioning health code systems. These apps or mini-apps are supposed to show whether or not the user has recently visited “hot zones” with active Covid cases. This is done by generating a QR code which can theoretically be scanned – though in practice no-one ever scans them. The problem is that those codes often fail to generate. In everyday life this is not a big problem, because they are seldom required. Where there are active outbreaks it can however be a big problem. Soon after the start of the Xi’an lockdown on Dec. 23rd, 2021, the Xi’an city government’s health code system broke down and stayed down for quite some time. In theory no one could enter any buildings (or the subway!) for an entire day. Upon investigation, it was discovered that the city government had given the development contract to a single source vendor without putting out a tender. Judging by the results, it’s clear that factors other than reliability were key to winning that contract.

It is still possible to walk into a Chinese bank with the equivalent of $500,000 in cash and deposit the bills no questions asked. However, if you deposit large sums three days in a row at the same bank branch, the third time the bank is now required to ask the source of funds and report it. Wire transfers exceeding 200,000 yuan now also get reported to the central bank. Small businesses still pay no profit taxes, so they are not required to report income to the government. For individuals there is also no general requirement to keep financial records or file annual income tax returns. The concept of an expense being ‘tax-deductible’ does not exist.

The English Wikipedia article on Yuan Tengfei is fairly objective: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yuan_Tengfei. Another excellent English-language article appeared in 2008 on danwei.org, still viewable here: https://archive.fo/NwBh. Yuan Tengfei still regularly produces content posted on his YouTube channel https://www.youtube.com/c/tengfeiofficial. While YouTube and Twitter censorship of posts and videos in Western languages is just as stifling as the censorship exercised by their Chinese counterparts, censorship of Chinese language content is rare. This makes these niches into rare bastions of free speech in an increasingly unfree world.

The English Wikipedia article on Gao Xiaosong is quite dishonest. It claims that he “is a pro-democracy activist in mainland China.” Neither of these is true. Gao Xiaosong lives in Los Angeles, and was certainly never a “pro-democracy activist.”

In 2013 the new central government under Xi Jinping imposed a mass one-time rotation of officials from province to province, ostensibly with the target of combatting corruption. As a result, in many places the system more or less froze for an entire year, during which time very little was accomplished. Perhaps as a result of this, this incident was not repeated.

In comparison to other provinces, not in any absolute sense. Generally speaking, efficient bureaucracy is not a Chinese tradition. Shanghai officials do however often get exported to other provinces when things go south. This is for example what happened in January 2020, when several top Shanghai officials were sent to take over running Hubei province.

In 2021 by contrast, government spending was around 37% of GDP, of which 7.5% was deficit spending.

As of 2020, the total value of China’s residential real estate was conservatively estimated to have reached 400 trillion yuan, or approximately $61 trillion, making up over half of total wealth held by private households. Due to real estate transaction taxes, these numbers probably understate the real values by approximately 20%. Though total estimated household wealth in the US remains slightly higher than the equivalent number in China, according to research published by Zillow, in 2020 the total value of residential real estate in the United States was only around $33.6 trillion.

Didi’s management informed the CSRC, but apparently never received an answer.

That year Guomei founder Huang Guangyu (黄光裕) was #1 on the Forbes Top 10 rich list. In 2010 he was sentenced to 14 years in prison plus $120 million in fines for stock price manipulation. He was released from prison in 2020.

This was an enormous fine, even for Alibaba. Barron’s published an accurate article on the questionable fairness of these fines on Dec. 15, 2021. See: https://www.barrons.com/articles/chinas-anti-monopoly-crackdown-is-just-an-excuse-51639513574.

“Today's banks continue to act as if they were pawnshops, holding collateral in return for credit. This was a very powerful idea 100 years ago; without these innovations, the Chinese economy could never have developed to where it is today. […] However, this pawnshop-based concept of finance cannot possibly meet the demand for finance in the next 30 years of world development. We must replace the pawnshop idea with a credit system based on big data with the help of today's technological capabilities. This credit system can’t be based on IT or on personal relationships; rather, it must be based on big data. Only in this fashion can we make credit equal wealth.” (Jack Ma in Shanghai, Oct. 24, 2020):

Readers wishing to learn more about Wei Ya and her rise to fame can check out this 5-minute mini-documentary with English subtitles on Youtube (Youtube locator Ao5mpDhXOKo):

If we look at the lack of respect for judicial decisions in many European countries during 2021, it must be said that many of these countries have already degenerated to point where they lack even basic respect for the rule of law.

As a case in point, on January 1st, a pregnant woman in labor was prevented from entering a Xi’an hospital due to her lack of a recent PCR test. As a result, she lost the baby, and ended up almost losing her life, as well. As terrible as this story is, it is nonetheless tempered by the fact that the responsible parties, in this case the hospital director and two other involved managers, were held responsible. All were suspended on January 6th. The heads of the Xi’an local health department head and emergency services received ‘serious warnings’. See https://www.shine.cn/news/nation/2201060493.

Such behavior on the part of government officials is of course neither new nor unique to China, as countless doctors in the West discovered in the past two years when they attempted to prescribe ivermectin or hydroxychloroquine to their patients. The key question is the same: to what extent is such behavior tolerated by government and society at large?

Statistics from 2017. Source: 2019年中国民营经济报告, https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1647322086137116909

These include Vanguard, Blackrock, State Street and many others, many of which seem, to a large extent, to own each other. Blackrock’s largest shareholder is Vanguard, and its second largest shareholder is itself. These funds also manage mutual funds whose shares they vote. Blackrock’s CEO Larry Fink is the most public face of this group, hereafter referred to as “Blackrock” for simplicity purposes. The real beneficiary shareholders are not a matter of public record.

This article provides several examples: https://www.businessinsider.com/what-to-know-about-blackrock-larry-fink-biden-cabinet-facts-2020-12

Blackrock, Vanguard and their other associated funds also have massive stakes in leading European companies, but the degree of control in Europe is much less well documented. They also have some stakes in Chinese companies listed overseas, which the Chinese government seems to regard with great suspicion. However, in percentage terms, their Chinese holdings are insignificant.

Informative, thought provoking and sobering for such a short piece. The only aspect of China's (and everyone else's) future ain't what it used to be, the Trillion pound elephant in the machine as it were, is of course A.I. (人工智能) with its 300 million and growing surveillance cameras among other unknown and perhaps unspeakable aspects. Just as the nose knows so too the subconscious. But yes, that's a whole nother story and deserves an ongoing expose of its own. What was it Putin said to the students not too long ago? Ohhhh riiiight, "whoever leads in artificial intelligence will be the ruler of the world" No small hyperbole, that.