Background Info Part 2 - Society & Quality of Life

What's life in China really like? What are the good and the bad parts?

View from China with an Austrian School of Economics Perspective

Conveying to Western readers a feeling for how life in China differs from what they are familiar with inevitably requires not only describing China, but also in some cases pinpointing those elements of “Western” life which differ dramatically. The fact that there are also significant differences between Western countries themselves makes this hard to do in a brief space.

Perhaps the most glaring difference is confidence in the future and the economic factors which lead to these differences. To illuminate this particular point, we will focus mostly on a comparison with the US. This post is not specifically about money and the economy, but to convey this important point, it’s unavoidable to cite some numbers.

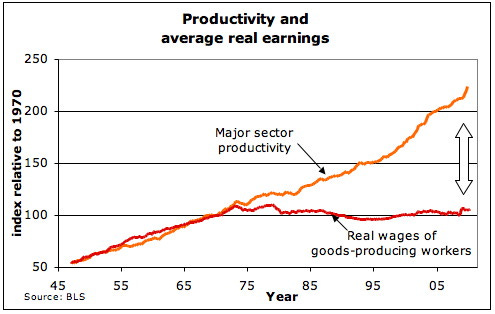

In the US in particular, for the bulk of the population, wealth and income levels have not improved significantly over the past decades. Whereas in 1974 most US households could maintain a high quality of life with one wage earner, now it’s increasingly difficult to get by with two. While the wealthiest 10% of Americans have fared very well, middle class purchasing power has plummeted. Poverty and crime are widespread and many households live from paycheck to paycheck.

At the same time, debt levels have increased dramatically, and it is quite common for people to be struggling with high levels of credit card debt. Between 2010 and 2020, the average US household savings rate hovered around 7%.

In China by contrast, both wages and wealth levels have soared over the past 30 years. Savings rates have never dropped below 27%. Keeping in mind the fact that China neither requires the filing of income tax returns nor taxes small businesses on the basis of profit or turnover, the real numbers are a matter of conjecture. However, if we use the official government numbers as the best available proxy, between 2010 and 2020 the average savings rate for Chinese households was around 38% of income. During the same period, income quintupled in nominal terms. Since the consumer price index rose by approximately 50%, the actual increase in real terms was around 3.3x.

The result? According to a Pew Research survey carried out in 2007, 83% of Chinese reported being “satisfied with the way things are going,” compared to 25% of Americans, 33% of Germans and 22% of Japanese1. Chinese levels of confidence were the highest of any country in the survey. These are stark differences. Though Pew Research does not seem to have repeated this question in the exact same form again, figures from other similar surveys carried out in later years seem to indicate that since then there has not been much change.

The existence of and/or lack of confidence in the future colors everything. Though few Chinese are satisfied with ALL aspects of the society in which they live (see bullet point #6 below for an example), for the most part history has led them to believe that things will get better and better. Not only do most households have hefty savings accounts and significant property wealth, they also see better roads, faster trains, bluer skies, far less corruption and, in most cities, almost a complete disappearance of violent and petty crime. Even 7 years ago, while there were already lots of well paved motorways, roads in many third tier cities were full of potholes. Outside the cities, sometimes motorway exits led directly to dirt roads. Today this has changed dramatically. These very visible improvements directly impact confidence in the future.

Perhaps the other major difference with much of the West is the lack of an underclass. Today there are very few poor people in China, at least not in the Western sense of an impoverished group of people living hand to mouth. So there are also none of the societal problems typically associated with poverty. Crime of course exists but violent crime and theft are rare. Yes, this is a generalization and there are always lot of nuances, as well as substantial differences between regions and urban / rural settings. But all in all, in comparison to violent countries like the US or many European countries with their enormous numbers of illegal immigrants, the difference is extremely palpable. Most major Chinese cities are among the safest in the world, with virtually no violent crime or theft. Every day you can see piles of packages stacked up on the sides of roads without any supervision. These are interim stockpiles of packages destined for delivery somewhere. Since such piles are so common, we can be fairly sure these packages are almost never stolen. It is worth noting that this is possible only because there are also basically no illegal immigrants. Pre-2020, China was open to visitors, family members, teachers and white collar managerial staff, but NOT to illegal immigration. (Now it’s open to no-one but residents.) When asked about the freedoms China has on offer, the freedom to walk the streets at all hours without having to fear assault or robbery is a big one.

With that in mind, here are some other important aspects of contemporary Chinese society:

1) No “social credit system”.

The entire “social credit system” narrative is a Western fabrication and likely a psyop targeting the West rather than China. Either that or it is SO secret that no Chinese living in China have ever heard of it, in which case one would have to wonder what the point is. What’s the use of having a social credit score if no-one knows his score??

Readers who have been exposed to this narrative should ask themselves: Why, with all of the thousands of articles written on the topic, plus countless videos made, do none of these articles or videos SHOW this alleged social credit app? What does it look like? What is it called?

Dealing with this topic in any detail would exceed the scope of this background post, but it must be mentioned because otherwise such preconceived beliefs risk coloring almost everything else. Credit rating systems do exist, though they are far less developed than comparable systems in many Western countries and certainly don’t involve rating people based on their proclivity for obeying rules. Some are run by the government, while others are run by private companies such as Alipay. Most of the government systems can be accessed via the creditchina.gov.cn website, though bizarrely the site home page does not always work. This link seems to be more reliable. There you can, for example, search for companies blacklisted for failing to pay their workers, or for companies blacklisted for illegal fund raising. You can also check to see if someone is subject to travel restrictions, though this requires the person’s ID number. Travel restrictions can be imposed on people who have court judgments against them personally, or against companies for which they have legal responsibility. (Normally this only happens if the court believes that the person in reality has the means to pay but simply refuses to do so.) Via other third party applications it is also possible to check to see if the CEO of a particular company is travel restricted. This can be very helpful when deciding whether or not to do business with a company. If their CEO is travel restricted, then you can deduce that the company’s commitment to satisfied customers might be weak.

Readers encountering this counter narrative for the first time may understandably not be willing to take our word on this. Fair enough. So suffice it to say that at this point at a minimum we merely suggest that readers not ASSUME that it is part of the landscape. We will address this topic in a separate post at a later time.

2) Water, air and soil pollution are issues, but with significant improvement since 2015.

On February 28th, 2015, Chai Jing, a former anchorwoman for China’s CCTV, released a documentary on China’s air pollution problem (English title: “Under the Dome”). Unsurprisingly, the government did not come off looking very good. Cleverly, she released it on a Saturday, streaming it on 2 of the top video platforms plus on the People’s Daily website, predicting that the government would likely not get around to processing it until the following Monday. However, by Sunday evening, the first limitations cropped up – comments and reports about the documentary were blocked. While some government officials expressed support for Chai Jing’s work, within days it became clear that the highest levels of government considered it to be too much of a loss of face. At the end of the week it was finally banned. By that time, however, around 300 million people had already seen it.

In 2015 air pollution was a significant problem throughout China, with Northeastern China including Beijing being the most severely impacted. Under the Dome proved to be a major catalyst for change, because it (a) clearly enumerated a list of causes, and (b) showed that the government was aware of most of them but had failed to act. In one segment of the film the head of China’s Environmental Protection Agency stated that he would be delighted to take action but that his hands were tied. Unsurprisingly, two of the primary culprits turned out to the two largest state-owned petroleum companies, as well as state-owned coal burning facilities. Despite the ban on the documentary, decisive action was taken, and today air quality is drastically improved, to the point where air quality in many Chinese cities is consistently in the good to excellent range (0-100). Shanghai numbers are exceptionally good, with AQI according to Apple’s Weather app on most days in the 20-40 range. On this topic, it’s important to remind readers yet again to be alert to the problem of fake reporting. Fake news is omnipresent. Specifically in this case, there are some websites which report radically higher numbers: A prominent example is the aqicn.org site, whose numbers are usually about twice what most other sites report.

After the release of Chai Jing’s documentary, the Chinese government passed a number of environmental protection laws, and made “environmental protection” into one of its primary themes. In particular, an air protection law was passed in 2015, a water protection law in 2017, and a soil protection law in 20182. Clearly some real progress has been made, but no doubt there’s a long way to go.

To cite just one example, soil contamination is a real problem in most former socialist countries, and China is no exception. The government has formulated a plan to restore the contaminated areas, but the estimated cost is over $1 trillion. However, this fact should not be misunderstood to imply that ALL Chinese soils are contaminated. Nor should it be conflated with the issue of food safety. Most soils contain some contaminants; the key question is, what ends up in the crops grown on those soils. China has an extensive spot checking program to monitor food toxicity, with public reporting of results. On their website results for individual brand names and product categories can be checked. They also operate a call center for complaints related to food toxicity. The responsible government agency is the Market Supervision Agency (市场监管总局).

Has this supervision led to a complete elimination of issues? Probably not, but in cases of systematic and intentional adulteration of food, it is a fact that the consequences of getting caught can be drastic. The most well-known example of this is the melamine adulteration scandal which became public in 2008. 21 dairy companies were found to have been using melamine, a dangerous additive, to enhance the protein content of some of their products, and in particular infant formula. 6 babies died from kidney stones and other kidney damage and an estimated 54,000 were hospitalized. A number of trials were conducted, resulting in two executions, three sentences of life imprisonment, two 15-year prison sentences, and the firing or forced resignation of seven local government officials as well as the head of government food safety agency at the time.

It’s worth keeping in mind that Western reporting about food adulteration in China also includes many falsehoods. A good example of this is the alleged sale of so-called “plastic rice”. In November 2016 the UK’s Daily Mail published one version of this story, though admitting that it was an unsubstantiated rumor which did not seem to make much economic sense. Both Snopes and the BBC reported that the story was fake.

China banned most GMO crops over a decade ago. A few products which include GMO ingredients do exist, but all are marked as such and tend to fetch lower prices than products without them.

3) Traditional concepts regarding gender & family.

There are no 59 genders. Just the old fashioned two genders. Families are fairly traditional and often multi-generational, with many accepting elderly parents into their households.

4) No government support for racism.

There is no government-promoted or supported anti-white, anti-black or anti-Asian racism. China not only has 1 million+ legal foreign residents, as well as hundreds of millions of internal migrants, but also 50+ officially recognized minority groups. Are some individual Chinese racist? Sure. For example, on occasion Chinese have been known to discriminate against blacks, and there were some nasty incidents in early 2020 when fear was at its peak. But to our knowledge the central government always explicitly condemned them and rebuked the officials involved. Racism is always publicly condemned, never endorsed, unlike what we see with critical race theory in the US today.

5) No politicization of everyday life, but a palpable generation gap.

No-one for example would say: "That's just right wing / left wing propaganda." There is no division of society into ‘us and them’. There is nothing even remotely comparable to the ideological divide in the United States and many European countries. Most people are completely apolitical. This is because (a) there are neither political parties nor electoral campaigns, (b) there is no organized campaign to change or abolish traditional values, and (c) few Chinese perceive the government as having much direct influence over their lives. To the extent that people have contact with governments officials at all, it tends to be limited to local officials enforcing petty rules – such as the health department in the case of small businesses. The government does not pay welfare and policemen have no incentive to accost people. Individuals pay taxes indirectly via value added tax paid by larger businesses as well as payroll and social security taxes paid by their employers, but there is little perceived direct financial interaction with government.

There is however a palpable divide between generations. Whereas older generations retain a memory of poverty and the abject failure of socialism, most young people lack all such experience. It is thus much easier to promote socialist ideology to them. And bit by bit, this is exactly what the government is doing. In reality of course, indirect government influence on people’s lives is enormous, especially if they elect to send their children to government schools. But remember, we are talking about perception here, not reality.

6) Increasing levels of censorship affecting social media, news sites and individual content creators.

We will address this issue at length in a later post, but it must be said the deterioration of freedom of public speech after 2020 has a chilling effect on the ability of Chinese citizens to work together for a better today and a better tomorrow. While it’s true that the censorship is often somewhat clumsy and not very quick, the effect on society remains. Just to cite two examples, this year the government fined Douban.com 20 times for a total of 9 million yuan. The government also forced the app stores to remove Douban’s mobile app. China largest blogging site Weibo.com was fined 44 times, with total fines amounting to 14.3 million yuan. As designed, such financial punishment leads these platforms to exercise extreme levels of paranoia in blocking any content which might somehow conceivably be perceived as politically incorrect.

7) High levels of convenience in everyday life.

China is the center of world production for many items, which means that for the most part China enjoys the lowest prices and shortest supply lines of any country in the world. This is reflected by the breadth of offerings on Chinese world-leading e-commerce platforms Taobao and JD.com. (Taobao belongs to Alibaba.) While there are always some country-specific items which cannot be found, for the most part the breadth of products significantly exceeds what is available on Amazon in the US, including drugs and supplements which are often either banned or strictly controlled in the West.

In terms of convenience, the other aspect is time to delivery. Due to high levels of population density in most Chinese cities, many items can be had within ½ day of ordering.

And while hundreds of millions of products are delivered every day, what actually dominates China street scenes are motorcycles delivering orders of prepared food. It’s a fair guess that there are as many orders of food as there are of products. White collar workers will sometimes go to lunch at local restaurants, but just as frequently they order takeaway. Prepared food is for the most part amazingly low priced, such that most households could afford to order out every day if they wanted to.

All of these items, as well as practically all other purchases of goods and services, get paid for using one of the two privately owned and operated payment systems: Alipay or Wechat. Thus far all attempts on the part of the plodding government-affiliated banking cartel to intrude on this duopoly have failed. Payments are made exclusively using smartphones. Credit cards are almost never used, and even bank cards are rare. Cash can still be used in most cases, but it’s increasingly rare for everyday purchases. While there are obviously some potential privacy issues, most people clearly opt for convenience over privacy.

See https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2007/07/24/chapter-2-global-publics-rate-their-countries.

See https://www.iisd.org/articles/toxic-soil-china for a discussion.

"Keeping in mind the fact that China neither requires the filing of income tax returns nor taxes small businesses on the basis of profit or turnover" - small businesses do seem to incur some tax although it is lower than in many Western countries, for example corporation tax for companies with under CNY1m turnover is currently 2.5% of profits https://taxsummaries.pwc.com/peoples-republic-of-china/corporate/taxes-on-corporate-income and personal income from an unincorporated business is taxed progressively at rates from 5% to 35% https://taxsummaries.pwc.com/peoples-republic-of-china/individual/taxes-on-personal-income .

Regarding tax returns, there may be no need to submit one for employees whose full income tax liability happens to be processed through their employer's payroll, but others will need to; this system is the same as the UK for example. https://taxsummaries.pwc.com/peoples-republic-of-china/individual/tax-administration