The good and bad of China’s medical system – Part 1

A commentary by EL: Why is it so hard to get a diagnosis?

View from China with an Austrian School of Economics Perspective

First a warning: This post is for readers who suspect there might be more to medicine than the “standard of care” taught in today’s “Western” medical schools. For the rest, read on at your own risk!

Many of the expats who have been in China for a while will remember the Good Old Days, when visits to Chinese hospitals were often a mixture of high danger and dark comedy. Some of the stuff that went on was so absurd that it would have to count as hilarious if it had not been so dangerous.

I don’t think I can ever forget my first experience in a Chinese hospital, when a foreign classmate of mine fell ill with pneumonia. He was in pretty bad shape and – according to the doctors – at risk of death. At least at the time, Chinese hospitals didn’t provide 24-hour care, so watching over him at night was up to us, his classmates. One night, the on-duty nurse told me that his blood pressure was very low and that I should watch the monitor and let them know if it dropped below a certain level.

Sure enough, around 5am in the morning that’s just what happened. Of course I rushed to the nurse’s station to let her know.

Now imagine what the nurse told me.

Did she hurriedly call up a doctor? Nope. The doctor was asleep.

Instead, she told me to wait until 8am when the doctor was scheduled to start his shift.

Me: “But didn’t you tell me he is at risk of dying with his blood pressure this low?”

Nurse: “Oh, that machine isn’t very reliable anyway.”

Amazingly, my classmate survived.

These days, things aren’t quite as absurd as they were back then, or at least not with the same regularity. Nonetheless, it isn’t always pretty and can still be quite frustrating.

Given the central role it plays in everyone’s wellbeing, one would imagine that at least somewhere on the planet some rich country would have a competitive medical system with the kind of excellent results we can expect from a free market solution. I have experienced quite a few countries’ systems, but if there is such a country, I am not aware of it. The opposite is almost always the case: The heavy hand of the state restricts access to medicines and medical devices, restricts the ability of medicine manufacturers to describe how they work, restricts the right to practice medicine and in the process massively increases the costs involved. In many countries – including China – the state also finances a system of public hospitals. These distort the market and in many cases make it difficult for the private sector to compete.

Curiously, support for freedom of choice in this part of the economy seems in most countries to be lukewarm at best, with many enthusiastically supporting all these restrictions. Heaven forbid the state should permit the free market to sniff out the best solutions! Alas, for better or worse health is a domain where most people hesitate to think for themselves and actively seek out an authority to make decisions for them. This preference on the part of the majority of course typically leads to inferior solutions for everyone, not just them.

On this account it should be said that in some respects Mexico does deserve an honorable mention. With its highly restrictive importation regime and limited availability of alternative practitioners it’s hardly perfect, but it DOES have a vibrant market for medical services, with not only a number of private hospitals but also countless private clinics with a range of specializations. Just to cite one example, once upon a time China was the world’s top go-to place for (mesenchymal) stem cell treatments, but sometime around 15 years ago a decision was made to limit access to treatment to high-level party members. Mexico eventually took up the slack. Mexico is now the world’s top destination for such treatments, with the lowest prices and the widest selection.

Though conditions have arguably improved since the Wild East days, China’s medical system certainly remains a mixed bag, as most of us who live in China can attest.

For those who yearn for more of the dark comedy on offer back then, check out the flashback essay from 2008 which follows this article.

The Good

On the plus side, China does have private hospitals. So there is some competition. And China has very reasonable pricing, with medical care available at prices which literally almost anyone can afford, even without insurance. Once upon a time price gouging was widespread, but these days at least in the public hospital system, this seems to be considerably reduced1. Instead, as in many countries, the top game in town is to squeeze as much money as possible out of social security.

Despite this wastage, the government’s public insurance program only covers part of the population and China continues to have a functioning price system for medical services. Unlike in countries with socialized medicine like Canada, there are few waiting lists.

Moreover, unlike most countries around the world, China has not permitted the pharma mafia to use licensing to decimate traditional medical approaches. As a result, TCM2 remedies remain widely available and are often prescribed by doctors in combination with Western medicines. Unlike in the West, insurance policies do not discriminate against traditional medicine. And China does have some excellent TCM doctors…. if you can find them.

Nor is the medical care on offer at hospitals, at least technically speaking, of a low standard. Many hospitals have highly efficient systems which carry out tests extremely quickly and efficiently and produce reports online within hours. Blood tests, CT scans, sputum cultures, ultrasound, CT scans, MRI scans, PCR tests – you name it, all of China’s major cities have public hospitals with these tests on offer, typically at very reasonable prices. (In fact, as we shall see, tests are so cheap that they have ended up in many cases replacing thinking on the part of the doctors, which can lead to poor results.)

One of the most illiberal aspects of the medical system in most of the industrialized world is the iron grip on medications maintained by the state and the drug-prescribing medical cartel. In this respect China is one of the most liberal out there, offering ready access to both herbal and pharmaceutical medicine, including lots of medicines which are restricted and/or extremely expensive in the West. This was a major plus during the Covid years, where China was perhaps the only major industrialized country where it remained possible to purchase both hydroxychloroquine and ivermectin, the two legacy drugs which proved to be the most effective against Covid-19. A bottle of 100 6mg ivermectin tablets is freely available on Taobao for around 12 RMB including shipping, while 14 0.1g tablets of hydroxychloroquine cost around 26 RMB via Meituan Maiyao.

Antibiotics are also fairly freely accessible. Prior to 2020 they had become more difficult to obtain in China’s first tier cities, but these restrictions were rolled back sometime during the past three years. Now they are once again easy to obtain everywhere.

Even exotic items like rapamycin are freely available both in raw form and as a packaged medicine.

Finally, there is even a flourishing black market for restricted treatments, for example for the mesenchymal stem cells mentioned earlier. After a hiatus of about a decade, such treatments are now once again available from multiple providers, with 100 million stem cells in IV form now reputedly available for as little as 20,000 RMB. While this is still about 50-100% more expensive than the cost of comparable treatment in Mexico, at least it is available.

As a result, for those satisfied with a DIY approach to medicine, China is arguably a paradise.

The Not-So Good

If however at some point, DIY doesn’t work for you, or stops working, then China starts looking a lot less attractive.

Why?

For one thing, China has relatively few “clinics” and basically no independently practicing doctors. As in many countries, this lack of supply is caused by restrictive licensing practices. This has led to a severe imbalance between supply and demand, i.e. in this case curing people of their diseases.

Second, as we shall see, what is left of China’s native medical traditions is arguably not in good shape.

These two factors may well be at the root of China’s problems, but on the front line they translate into more concrete issues. I’m sure I’m missing some, but here are the top four issues (as I see them) affecting the official medical industry:

1. A lack of general practitioners (全科医生), and more generally, an almost complete lack of holistic doctors with a big-picture perspective.

2. A systematic failure to listen to patients, and in that context, an overreliance on tests.

3. An abysmally low level of knowledge about gut issues (i.e. IBS and the like), food allergies and the relationship between the two.

4. A lack of interest in the underlying causes of illnesses and in this context, a corresponding lack of knowledge about treatments of the underlying conditions.

The result of the above four issues is twofold:

A general weakness in coming up with accurate diagnoses, and

A persistent failure to treat the causes of sickness.

I will address the above issues and their consequences in the next section.

Before we get to that, however, there are three more contextual issues which cannot be overlooked, since they are key to understanding the stagnation which characterizes the medical industry:

5. A lack of a vibrant domestic ‘health talk’ industry. Perhaps one could say that this is the lack of an open public dialogue about health.

6. A high level of dependence on the West for innovation in the health sector.

7. A complete disconnect between the formal Chinese medical community (including the TCM practitioners) and the Western alternative medicine industry. Some of these ideas do eventually reach China, but it tends to take a while, and their integration into formal Chinese medical practice is patchy. I’ll give some examples below.

While there are a few KOLs (大V) in the health sector with popular Wechat public accounts3, almost all of these tend to be practicing doctors within the public health system. How far can these doctors on the state payroll go when it comes to talking about new approaches? Probably not very far, because almost any discussion of ‘new’ approaches invariably can be seen as criticism of the status quo. Speaking up about touchy topics has led to quite a few getting themselves cancelled, so the rest have presumably learned to hold their tongue.

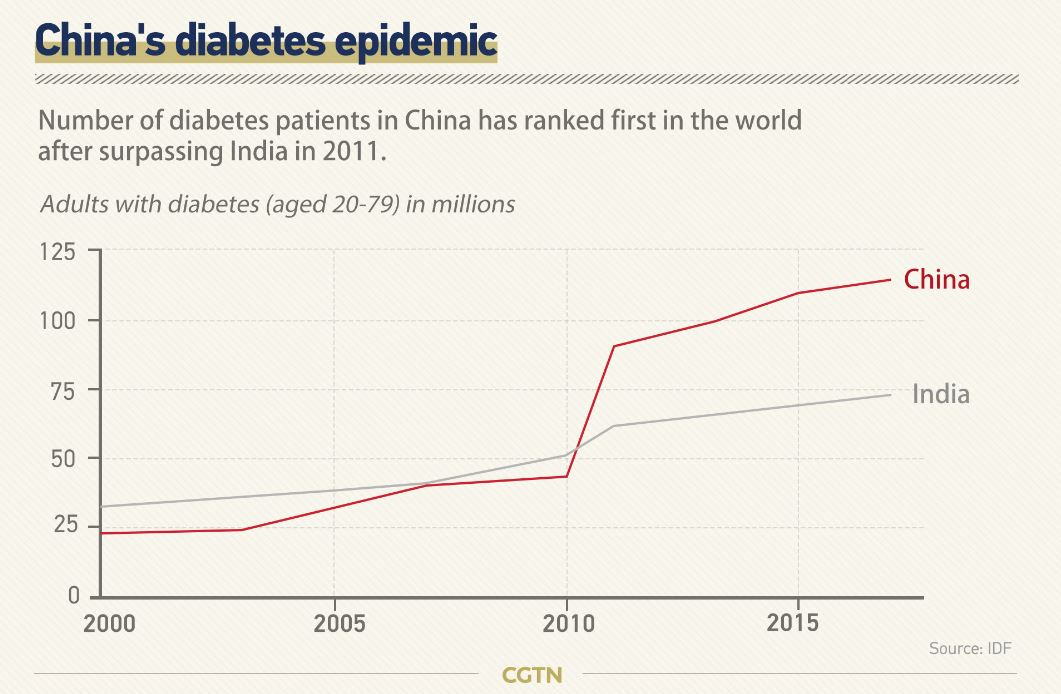

If we take diabetes as an example, given that an estimated 10% of all Chinese are sufferers, why aren’t there scores of KOLs talking about causes and solutions for them? What is causing this epidemic? What can be done to bring down these numbers? What can be done to reverse these conditions? Why are so few sufferers changing their eating habits so as to avoid the need to inject insulin? In 2021, an estimated 141 million Chinese were suffering from diabetes, so this is not a minor issue. According to an estimate published by CGTN in 2019, on average Chinese diabetics spend 20,000 RMB per year on treatment. By implication, this means that the overwhelming majority of these are dependent on insulin injections. By any normal logic, this discussion should be attracting enormous attention and resources, no? Sure, there are blogs and product hawkers, but where is China’s version of Dr. Mercola?

The same could be said of cancer. Or of auto-immune issues. Or of gut issues and food allergies.

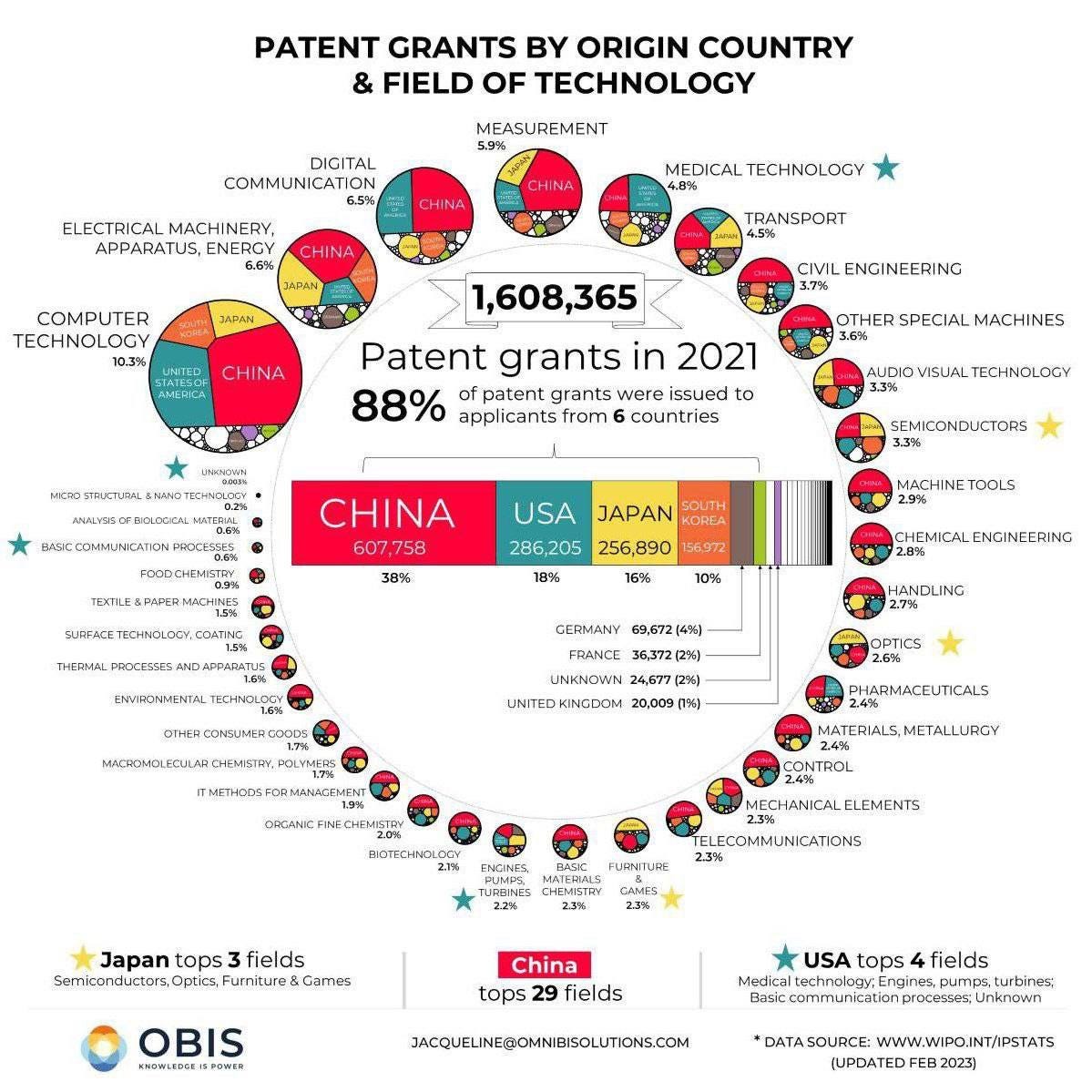

If we look at innovation within the health sector, even when it comes to innovation based on traditional TCM ideas, like, say, electro-acupuncture, these innovations have for the most part come from the West. When was the last time a new health promoting innovation like, say, the ketogenic diet (生酮饮食), stem cells (干细胞治疗), or to cite a less well-known one, bio-resonance, sprang up in China and made its way all around the world? To my knowledge, the answer is never. (Readers, feel free to correct me!) Even buzzwords such as bulletproof coffee (放弹咖啡) all are imports from the West. How useful and groundbreaking these concepts and technologies are is a matter of debate, but the point is that that both debate and experimentation needs to take place for there to be progress. For the most part, that debate is not taking place in China. With more patents registered every year than any other country, China is the world-leader in innovation in many areas. Yet not when it comes to health. Why not? This is a question that must be asked.

Can I get a diagnosis please?

A number of my experiences provide apt illustrations of this dismal state of affairs. I’ll start with one which actually took place over a decade ago.

At the time I had a gut issue. I had occasional splotches of blood on the backend and accompanying feelings of illness. There was something severely wrong inside and it clearly wasn’t getting better on its own. The problem was: where exactly inside? I knew from the observable symptoms that it was a gut issue, but that was not sufficient to find a doctor who could actually help.

I tried both public and private hospitals and eventually ended up doing a colonoscopy in a private hospital. This did not yield any useful results, other than to conclude that the problem was probably not there.

After much contemplation and online searching I eventually found a doctor in Vienna who gave me a useful diagnosis: leaky gut. In other words, the membrane coating the inside of my small intestine had cracks in it. Based on this diagnosis, he also correctly guessed that I had likely developed allergies to some of the proteins which had been leaking through the cracks. Identifying and avoiding those foods brought immediate relief.

How did the Austrian doctor figure this out? Well for one thing, he listened to me describe both my symptoms and how I got to where I was at the time. He did what is a called an ‘Anamnese’ in German. This word doesn’t even exist in Chinese. The dictionary translation for this is ‘病历‘ (bìnglì) — i.e. medical history — but that’s not really what Anamnese means. You can say something like ‘病史讲解’ but that’s more a description than a concept. It means using one’s medical knowledge and experience to probe the patient for clues as to his or her condition. For some reason, listening to patients is something that Chinese doctors are generally terrible at. This failure can of course have devastating consequences.

As mentioned above, the other factor in play is a general weakness in the area of internal medicine (内科), especially when it comes to gut issues. This is perhaps because although there has been enormous progress in this area in the West in fairly recent times, almost all of this progress was achieved by alternative medical practitioners. As a result, very few of these new insights ever reached China. In fact, even today it is quite rare to find a Chinese doctor who even knows what leaky gut is.

I was told that there was an old professor alleged to be a specialist in such matters, but the waiting period to get an appointment was about 6 weeks, and even then I had the distinct feeling that he was probably not likely to be cutting edge.

Many of the internal medicine people have heard of the term ‘Crohn’s’, which more or less refers to the same thing but lacks the descriptiveness of the term ‘leaky gut’, but they are not able to diagnose it and even with the diagnosis in hand, basically no-one has any idea how to treat it, much less cure it.

Luckily for me, there are ways to both treat acute flare-ups and to cure it, and eventually I figured these out. For example, the antibiotic metronidazole (Flagyl) is a super cheap and quite effective plaster. It doesn’t cure you, but it can make you feel a lot better fairly quickly. No-one in China except for veterinarians seems to know about metronidazole. It’s on the WHO list of essential medicines, but in China I have never seen it prescribed for humans – not once.

Curing yourself involves patching the leaks, plus avoiding the proteins which were leaking prior to your patching work. There is a pile of information out there in the Western Internet about how to do this, and some countries even tolerate holistic doctors who will help guide patients through the slow healing process. China might be prepared to tolerate them, but at this point, there is no-one to tolerate. This is because very very few of its doctors have this knowledge.

Ironically, some of the soil-based probiotics I made use of are actually more readily available in China than they are in the West. But you have to know. Since the products are available, presumably somewhere out there in China the knowledge must exist. But where?

Keep in mind, this is not some rare disease which afflicts a few people every year. There are tens of millions of Chinese, if not hundreds, who suffer from gut malfunctions.

Figuring all this out on one’s own takes time. And that’s assuming you eventually do. Millions never do and just have to suffer. Wouldn’t it make much more sense to have a medical industry capable of doing this?

Part 2: How China’s hospitals make do without general practitioners (GPs).

Follow us on Twitter @AustrianChina.

At private hospitals, most of which are outside of the public insurance system, obviously the patients remain the targets.

TCM = Traditional Chinese Medicine

People like Zhang Wenhong or Duan Tao. A Wechat public account (‘公众号’) is a public blog, these days to a large extent replacing Weibo in importance. Unlike say, Substack however, comments must all be approved.

Thank you very much for that article.

I strongly advice you to acquire and read Arthur Firstenberg, "The Invisible Rainbow" refering to what causes the 'epidemic' of heart diseases, diabetes and cancer. His point of view should really be taken into account. https://archive.org/details/the-invisible-rainbow-a-history-of-electricity-and-life-arthur-firstenberg-z-lib.org/The%20Invisible%20Rainbow%20A%20History%20of%20Electricity%20and%20Life%20%28Arthur%20Firstenberg%29%20%28z-lib.org%29/

I gave that link to a free access to his book but I think it is better to buy it so that his work be rewarded.

Take care

Respectfully

Lionel

A lot of those criticisms about underlying causes can also be applied to Western medicine. Alternative medicine practitioners may not be as hard to find, but because they're almost never covered by insurance, are out of most people's reach.