China's charms for expat parents: why China is still hard to beat

20 Years of Expat Life in Shanghai + Why Some Still Stick Around

View from China with an Austrian School of Economics Perspective

Despite the ravages of the Covid years, these days the world still has quite a few expats, i.e. people living and working outside their home countries. These include not only people sent abroad by their companies, but also foreign students attending local schools. It also includes ex-foreign students who choose to stick around after they graduate, as well as millions of others simply searching for a better life.

As one of the key players in the globalization process that helped drive this, China in general and Shanghai in particular are no exceptions. Despite a significant fall in numbers, both still retain quite a few hard-core fans (贴粉儿). In the following, we’ll take a look at what’s keeping those expats here.

Anarchist Utopia

Back in the aughts (more precisely, 2000-2008), China was in many ways a kind of anarchist utopia, the kind of place where a motivated entrepreneur could arrive and build an empire within a relatively short number of years. It was a place where anything was possible and bureaucracy limited. Word got around and ambitious young immigrants poured in from all over the world. In China’s first-tier cities, many service industries acquired a heavy foreign presence, and this is when chains such as Blue Frog or Wagas as well as highly successful websites like Qunar.com were set up.

This surge was reflected by the average age of expats in Shanghai. According to the city government’s 2014 Shanghai Basic Facts handbook, back in 2010 it was only 33 years old.

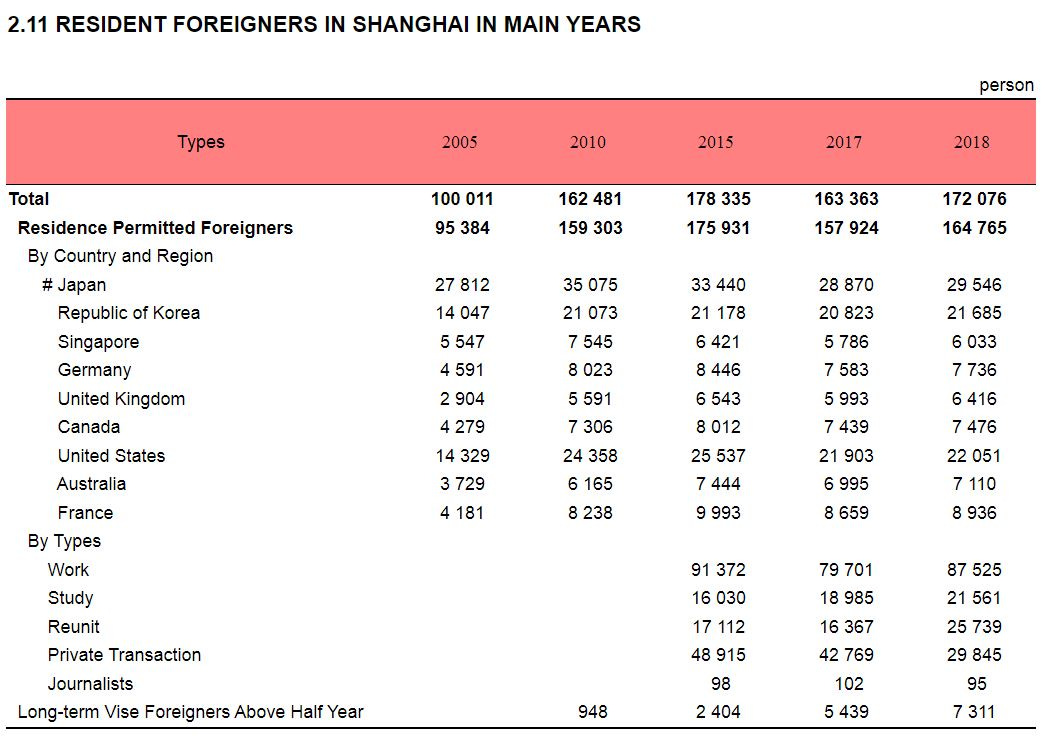

Despite a cooling of the often frenetic pace of the aughts, until 2015 numbers of resident and non-resident foreigners continued to nonetheless slowly increase. That is when the new left-wing government began to roll out a series of measures to reduce the number of visas issued. These included a long list of new restrictions for work visas plus the virtual elimination of the option to use F (访问) temporary work visas to accommodate paid interns. This had the result that in particular young foreigners (including those graduating from local universities) found it often all but impossible stick around and establish themselves.

This crackdown was then soon followed by crackdowns on nightlife areas catering to foreigners, as well as on the occasional crackdown on drug purveyors.

All in all, it was clear that the previously very inviting welcome mat had been rescinded.

Nonetheless, though the number of newcomers declined drastically, those already here tended for the most part to stick around. Most had jobs and many had already found local partners, foreign or Chinese. Many had children.

The Covid-era

Then came the three-year long Covid-era, during which China was for the most part completely cut off from the rest of the world, with virtually no international travel taking place. This ended up being a milestone and marked a definitive end to the previous era.

As we have discussed elsewhere, though Western reporting about events was often inaccurate and exaggerated, and China imposed neither nationwide lockdowns nor vaccine mandates, plenty of what went on in those three years was inhumane. Moreover, quite a few things happened which were in direct violation of Chinese law.

While one can argue that in some respects China was in some respects a relatively attractive place to spend those years (for example due to its lack of a vaccine mandate and the liberal access it offered to treatments suppressed in the West), this nuance was likely not so obvious to most of the expats in China at the time.

For more on this see myth #5:

How many foreigners are left?

Be that as it may, quite a few expats left China in 2022 and 2023, in particular many who were living in Shanghai when the city was locked down in April 2022.

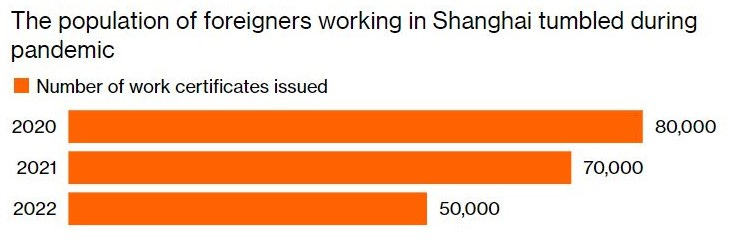

We don’t know how many exactly, since the government stopped publishing the numbers. However, if we look at the approximate numbers of work permits issued (roughly -37% versus 2020), we can guess that the number was significant.

Nonetheless, some foreigners stuck around, and some who were caught outside of China when China started sealing the borders in 2020 finally managed to return.

What’s keeping them here?

Night life is definitely not what it once was and the “laissez-faire pure” days are ancient history. Business confidence hasn’t been lower in living memory, and there’s a long list of viewpoints which are now unwelcome online – even though most of them end up getting expressed and passed around anyway.

And yet many expats, especially those with families, are still here. Here are a few reasons why, starting with the most obvious ones:

Some of the primary reasons for sticking around

1) Safety & high-trust society.

Violent crime, burglaries and street theft are extremely rare. Young people without experience in high crime countries can frequently can be seen leaving their computers unmonitored in coffee shops. Though there are some long-term downsides to this (for example when traveling to less safe countries), for families with kids this factor gets a lot of weight.

You are something like 70x more likely to be a victim of violent crime in the US than in China. Numbers in Europe may be a bit lower, but these days Europe is full of violence, while in China violent crime is basically unknown.

One reason for this may be the widespread use of surveillance cameras, both public and private, but that’s just a possibility, since violent crime was already very low prior to their introduction. Facial recognition systems may also play a certain role, but if so, it’s not clear how much of a role. The mere existence of a video record in so many places undoubtedly acts as a deterrent.

The other reason is however a simpler one: the low prevalence of poverty and the lack of a distinct underclass. Back in the aughts one might have argued that Uyghurs and migrant worker immigrants from rural China constituted two underclasses in many of China’s major cities. At the time, for example, many street crimes were carried out by Uyghur kids from Xinjiang (making use of the ‘too young to be charged’ out-clause). These days, by contrast, the remaining Uyghurs mostly sell fruit and run restaurants. As for the Han migrant population, with passing time, the lines between them and the local indigenous population are inevitably fading.

2) Low cost of living and high availability of almost everything, including many items whose sale is restricted in the West.

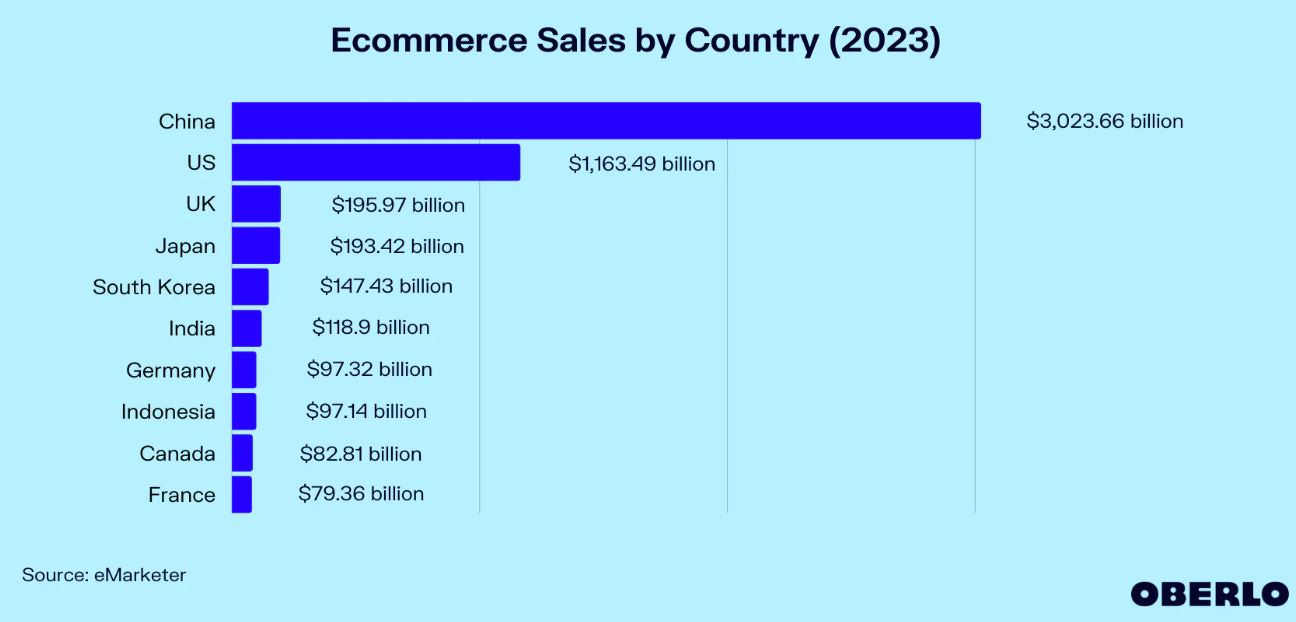

To grasp this, you have to try to appreciate the size of the Chinese economy relative to the world’s other major economic blocks. It’s literally the elephant in the room. The numbers speak a clear language: China has both the world’s largest productive GDP and the world’s largest e-commerce industry. It’s also at the heart of most of the world’s supply chains and thus drives much of its innovation. Those who doubt this final point should take a look at the list of the top apps for 2023 on Google Play (which is not used in China). Despite the fact that this list does not include downloads from users inside China, quite a few of these apps are Chinese. Patent applications tell a similar story.

In 2023 e-commerce sales in China exceeded US$3 trillion, almost three times the size of the U.S. market. Productive GDP measured at purchasing price parity (i.e. GDP without services) was also around three times the US level. As a result, aside from a few imported luxury items, Chinese residents tend to get better prices and a wider selection than people living anywhere else in the world.

Nor is this advantage limited to manufactured goods. Prices for food and services tend to also be a fraction of Western levels, with the gap growing every year thanks to high levels of inflation in most Western countries.

This extends to most medicines including antibiotics, as well, almost all of which can be ordered online and delivered within 30 minutes or less. Bio-hacking medicines such as rapamycin or nootropics can usually be ordered at prices which are a tiny fraction of those typically charged in the West; moreover, they are almost never banned or heavily restricted, as is common in the West.

In summary, from a consumer perspective, there is simply no other country in China’s league.

3) Ready availability of 24x7 childcare.

China’s tradition of live-in nannies at reasonable prices (9,000-12,000 yuan/month or approximately USD 1,260-1,680/month) is a huge plus factor for parents with young kids. For those expats with local spouses, live-in grandparents can also share the child-care burden.

4) Lackluster competition.

Even in the areas where today’s China has some serious issues, these days the West hardly shines in comparison. For example, many Western economies are also suffering from sluggish performance. But perhaps most prominently, freedom of expression in the West is also hovering around all-time lows, with dissidents frequently subject to harassment and even imprisonment. Moreover, in China no-one is being harassed for public support of traditional values.

We wrote about this global race to the bottom here:

Six key freedoms China has on offer

Though the above four reasons may be some of the more obvious advantages China offers, China also has a few freedoms on offer which can be decisive for some parents, in particular for those old enough to be aware of some of the more problematic aspects of contemporary Western society.

1) Freedom from obligatory schooling.

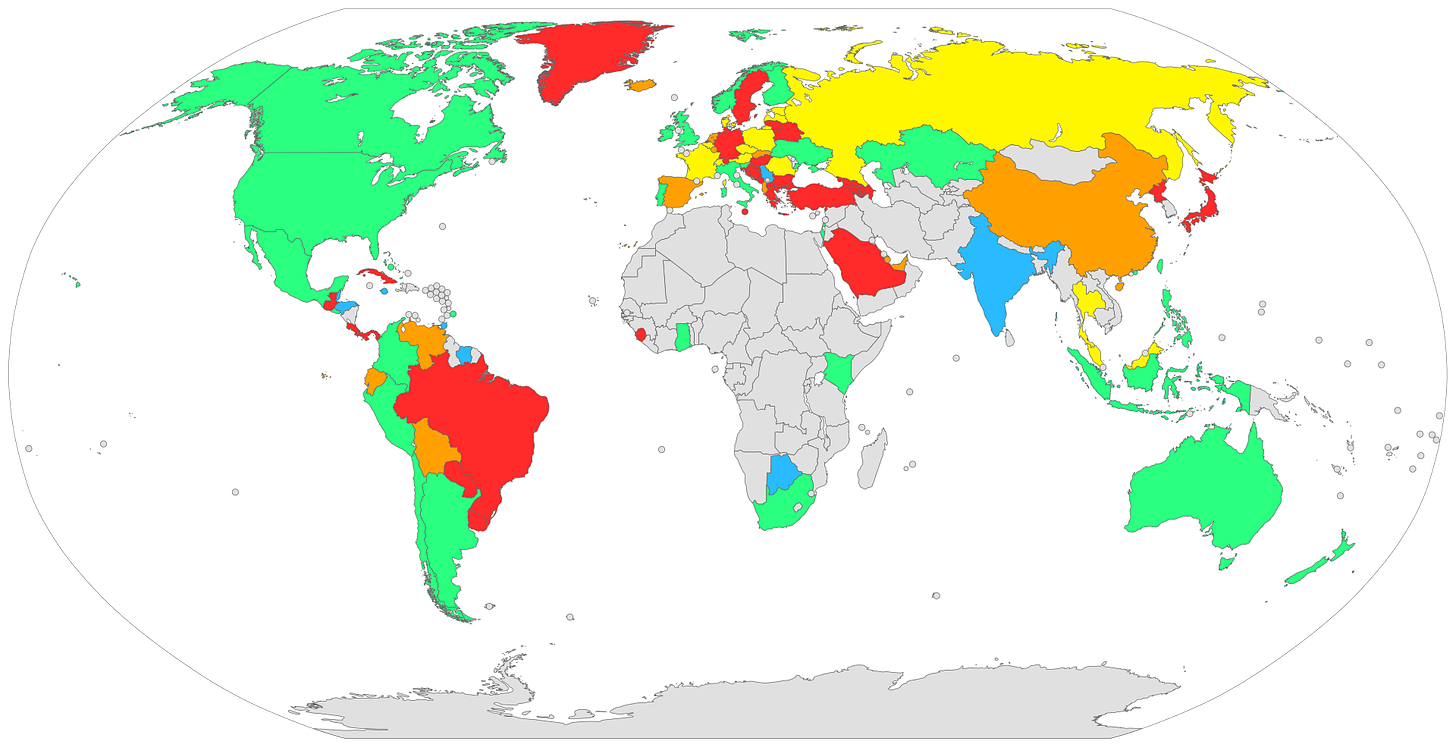

In some countries (like Germany for example) parents are required by law to send their kids to a government-certified school. In other countries like the United States parents can opt to do home schooling, but only if they register and are approved for this with their local government. In other words, it’s not an absolute right. In China, by contrast, the state does not interfere at all. Not only can parents opt for private schools instead of government schooling, they can also choose to forgo formal schooling completely without having to worry about satisfying some random government’s ideas about how best to go about educating their kids at home.

2) Freedom from “child protective services”.

In many Western countries children can be taken away from their parents based on often unproven allegations of abuse or a failure on the part of their parents to comply with various government-mandated “standards of care” – for example because the parents refuse to allow them to change gender or undergo chemotherapy.

To cite a few examples, in Germany each year approximately 15,000 children are taken away from their parents. In Britain, the annual numbers seem to be around 30,000 per year, though exact statistics seem hard to track down. The United States takes the top prize, where according to the Family Preservation Association, a whopping 400,000+ children are taken away from their parents every year, which amounts to over 0.5% of the total child population. According to this same source, an estimated 37.4% of all American children subject to a “child protective services investigation” before the age of 18.

In China there is no such system. If parents are found to have abused their children they can be arrested (usually after several warnings), but children are only relocated if no parent or relative is immediately available to take over their care. In most such cases (which are rare), children end up with relatives.

3) Freedom from illegal immigration.

China has basically no illegal immigrants. Tourists are welcome, but if you want to stay you need to get a job and a work permit. Inside China there are few controls on the movement of people, but border control is strict. This is in marked contrast with many Western countries, where decades of mass illegal immigration have led to the creeping undermining of previously high-trust societies.

4) Freedom from the “culture of dependency” mind virus.

To the extent that direct welfare payments exist at all, for those under the legal retirement age, the amounts are minimal. Shanghai has the highest in the country @ 1,510 yuan / month, but only if you can prove you are unable to work. This reflects CPC policy, which explicitly condemns the “welfare trap” (福利主义的陷阱 / fúlìzhǔyì de xiànjǐng).

Unemployment insurance exists in theory but payouts are so difficult to apply for that almost no-one ever bothers. Some hidden forms of welfare do exist (for example, via the public health insurance program), but these are in no way comparable to the kind of dole system which has grown deep roots in most Western countries.

The result: China has no culture of dependency. In other words, children and teenagers grow up in a society where it is considered indispensable that each person find a way to provide for himself and his family. Families are usually willing to help in times of need, but there is no expectation that the government serve as a backstop.

5) Freedom from woke culture.

For expats aware of how crazy things have become in much of the West, this can be a big deal. Kids are not being bombarded with LGBTQ+++ advertising or surreptitiously encouraged by their schools to change their gender.

6) Freedom from forced vaccination.

In China it’s up to the parents to decide. Many schools (both public and private) do demand vaccination papers, but plenty of kids in China remain unvaxxed and their parents apparently all found ways around those demands.

In Summary

Which points are important to which parents varies, but at a minimum China offers a very different set of conditions than its Western counterparts. The state has a far more standoffish attitude towards children, and this is reflected in many of the above points. All of this comes at price, of course. In particular, like many other East Asian countries with high population densities, private space is a premium item in China’s major cities, and most particularly in its four top tier cities Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Shenzhen. Thanks to China’s 25-year long building spree and a plethora of high-rise residential developments, indoor space built to a modern standard is no longer a luxury good; however, it’s not the same thing as a private house with a yard. Thanks to the rapidly expanding suburban highway and light rail networks, these are now available and accessible, but at a hefty price. China’s replacement for this is a network of attractive public parks, but clearly that’s not quite the same thing.

As always, all package deals come with pluses and minuses.

Support us by sharing your thoughts and following us on X and Substack @AustrianChina

Visiting Chinese tend to talk along with our perception of China as a communist dicatorship. Yet when you show an open mind they'll gladly explain China is freer than The Netherlands.

The graph you link shows The Netherlands has legal homeschooling. This is not practically true. Parents are required to send their kids to school ("leerplicht") with only 800 exceptions granted, mostly for professionals travelling abroad. Fines for not attending school are high and applied even to wealthy people who can afford a lawyer. Like you also mention, the threat of child protective services is real, everyone knows a case in their family, and enough to push people into compliance.

You keep on giving me more reasons for loving China!