View from China with an Austrian School of Economics Perspective

Is China a hellscape filled with people cowering in fear of a totalitarian government? Is it a socialist country run by a benevolent dictator? Or is it something else altogether?

Problems making sense of the world via social media

When it comes to making sense of the world, these days social media is where most people get their building blocks from, be it about matters of health, wealth, sports or what is going on in the rest of the world. If the topic is one with which the reader has personal experience, it’s a helpful tool, because the reader can use his own experiences to assess the additional data on offer:

Is it plausible? Does it fit in with my own experiences?

By contrast, when readers lack first-hand experience, new problems arise. Not only is it far more difficult to put the various pieces of data together, it’s far more difficult to spot fakes. This is because in lieu of direct personal experience, the #1 fallback criterion used tends to be repetition. Someone wishing to spread a lie, or a set of lies, need merely repeat them often with some variation, and sooner or later he will have a good shot of generating believers.

The four primary China narratives on offer by social media

This is the predicament faced by many Western observers trying to make sense of China. If their information source is Western social media, they generally have a choice between four narratives. Either China is:

(1) a socialist/communist success story proving the superiority of socialism/communism to the world, or

(2) an Orwellian hellscape where the population lives in fear of its all-powerful technically sophisticated totalitarian government, or

(3) an economic house of cards which is about to collapse any day, or

(4) can be summed up plain and simply as “CCP bad”.

The final narrative isn’t actually a narrative at all, but crops up so often that it has to be mentioned.

As we shall see, the Austrian perspective is that none of the above narratives bears any resemblance whatsoever to reality.

Narrative #1 – The Party Fan Narrative: China is a socialist success story

This narrative revolves around the government’s claim that China is pursuing “socialism with Chinese characteristics” (中国特色社会主义) and by implication is efficiently run by a benevolent bunch of top-notch central planners in Beijing. The government itself does not use the term “planned economy” (计划经济); on the contrary, its representatives have on multiple occasions explicitly emphasized that it is committed to the market economy. However, this doesn’t stop its fans from doing so.

Make no mistake; there is absolutely no question that modern China IS an enormous economic success story. In fact, it’s one of the most spectacular economic success stories in human history. But does it have a planned economy, and is it a socialist success story?

Inside China, the promoters of this narrative are often referred to as ‘小粉红’ (‘xiǎo fěnhóng’, more or less meaning party fans), with the implication of them being young. The term refers to their seeming willingness to accept and echo whatever narrative the Chinese government happens to be pushing at the moment.

Needless to say, not all of them are young. The ranks of this group do however thin out as they grow older and many realize that reality is not as simple or rosy as they had been told. Nonetheless, the overall numbers are substantial, a fact which should not be surprising given the general widespread popularity of the Chinese national government among the masses. This popularity has been confirmed over and over again by multiple polls by Western pollsters stretching back as far as 20 years ago. According to most of these (e.g. the Edelman Trust Barometer), for most of the past 15 years the Chinese government has been consistently ranked as the most popular government in the world — notably among its own citizens, not as ranked by citizens of other countries.

People are not stupid; for all of its faults and seeming incompetence, over the past 30 years the Chinese government has presided over one of the most spectacular explosions of prosperity in human history, with GDP growing by around 40x since 1992. Not only is absolutely everyone far far wealthier than before, but the skies are bluer, the trains are faster, the cities are greener and the roads are now among the best in world.

Note the term “presided over”. If Deng Xiaopeng is to be believed, the key was not central planning by bureaucrats in Beijing. That was what left China destitute at the end of the Mao era. What was going to make China rich was regionalization (empowering local governments to make their own policies to compete for investment) and letting people get on with business. To put it another way, the approach was to decentralize decision making as much as possible.

There are quite a few of these party fans both on Chinese social media and on Twitter/X; they are mostly Chinese but also a few foreigners. Their Western critics tend to call them ‘五毛党’ (50 cent party), because they are allegedly paid 50 Chinese cents per pro-party post. If that’s true, given the widespread subtle ridiculing of Chinese government policies on Chinese social media and demonization of the ‘CCP’ on Western social media, it would seem that the party isn’t paying enough.

Here’s an example of a recent X post promoting this narrative:

The problem here is that in reality “China” (which implies some government agency) is not the entity doing these installations. What Bloomberg NEF probably means is that so and so many chargers were installed in China. As written, this claim simply isn’t true:

At least in this case, we can’t blame Mr. Smith for this, since Bloomberg is the source of this misleading claim.

Moreover, this narrative for the most part reflects what the government itself is promoting.

Regardless of what the government would have us believe and despite its revived dabbling in central planning (see below), as we have extensively documented in previous articles, today’s China is not very socialist (or communist for that matter) by any standard normally associated with either of those words.

More on dispelling that myth here:

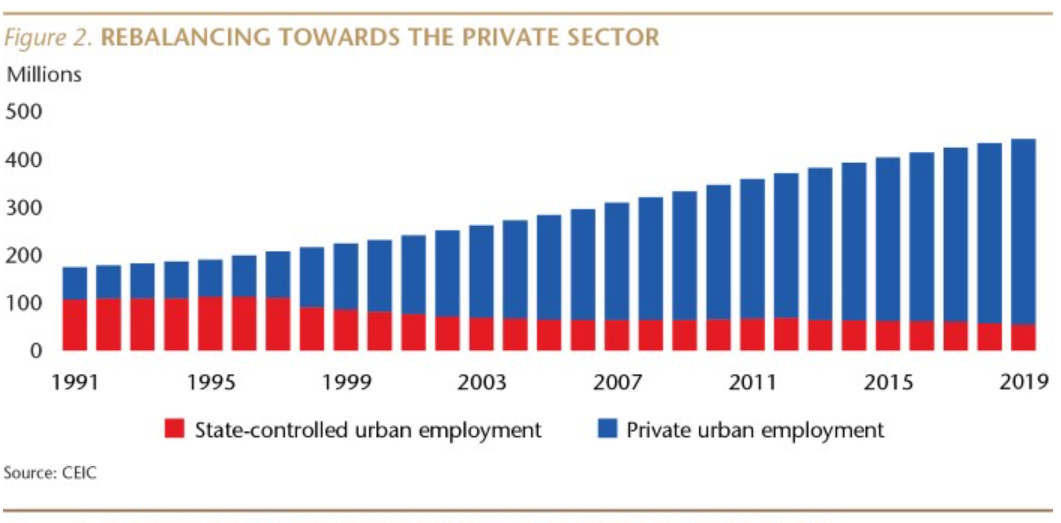

On the contrary, it has basically no welfare and a free market-driven economy with some of the fiercest competition in the world and an extremely high level of respect for property rights. It is overwhelmingly powered by privately owned companies, and the overall share of state-run companies as a percentage of total employment continues to drop every year. These private companies create around 75% of value added, 100% of new jobs, and generate over 90% of patent applications. By some accounts China has five times more dollar billionaires than anywhere else in the world outside the United States.

Moreover, there is absolutely no evidence that the Chinese government “controls” China’s privately owned companies. If it DOES control them, why does it treat them so poorly? Just to cite a few prominent examples: Tencent, Alibaba, Meituan, Didi, Douban – all are market-leading companies which in recent years have been assessed astronomically high fines, in several cases in excess of $1 billion dollars. They have also seen their apps banned from the app store (Didi), been forced to delist their stock abroad (also Didi), and had stock market listings stopped (Ali Financial). As a result, the stock market valuations of many of these companies have now shrunk to a small fraction of their previous market value.

Yet at least they are still in business, which is more than can be said for the countless companies who saw their business models destroyed by a sudden ban on their industry – such as those (previously) in the cram school, P2P lending or crypto industries. While a few of these companies managed to survive, most ended up having to close down, leading to the evaporation of tens of billions of dollars in value literally overnight. Needless to say, no compensation was ever paid.

We can be quite sure that the government wasn’t running these companies.

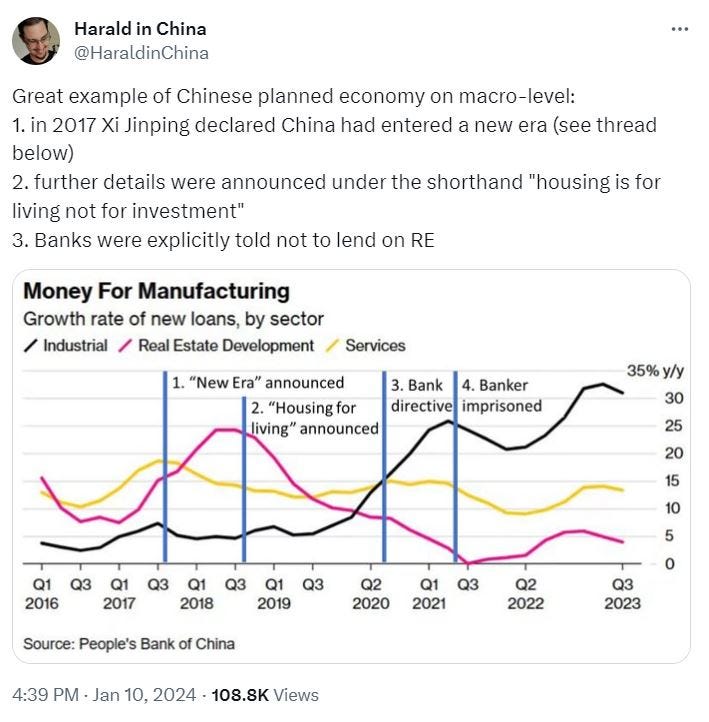

Let’s look at one more angle. Here’s a post specifically mentioning China’s “planned economy”:

This post does have a basis in reality: namely, the real aspiration of the current Chinese government to resume planning the economy, at least to an extent – despite the terrible results the last time around. In other words, up to a point it aspires to let bureaucrats instead of capitalists decide where investment will flow. Besides industry bans, the government’s primary tools to accomplish this are preferential taxation policies, preferential lending practices, and targeted investment funds (产业引导基金). These selectively invest in favored industries, such as the “new energy” (新能源) sector.

What goes unsaid is the huge gap between ambition and ability. Though industrial production numbers are up, especially in those favored industries, what happens when the subsidies for these products are suddenly eliminated or reduced?

Look at a heavily hyped company like NIO (蔚来汽车). Despite the fact that it has never generated a profit, its stock soared to $57 in 2021, with a total market cap of over $100 billion. Now its stock is under $8 and the company is on the ropes. This kind of pattern is a common one for companies dependent on preferential policies for their success.

Moreover, what about the effects on business confidence and the rest of the economy created by these preferential policies in combination with multiple cases of industry bans, crude attempts at manipulating stock market prices and the poor treatment of non-favored companies? If we look at the rock bottom level of business confidence and the depressed stock market prices, the net result is hardly impressive.

At the same time, this is not meant to imply that the Chinese government does nothing useful. It does do useful things, mostly financing roads, train tracks, train stations and the like, and these are certainly far more useful than, say, building rockets or bombs. Though all the related deficit spending has created some other problems, thanks to China’s super-competitive economy and the world’s most comprehensive and efficient supply chain, it now does these things fairly well. But this is not the same thing as a public sector-driven or a centrally planned economy. The employment numbers in the above table speak for themselves.

Nor does the fact that they have some not-so-smart policies, or that they try over and over again to indulge their central planning fantasies, negate the fact that they have also promulgated some demonstrably good policies.

None of the above however changes the fact that the “China is a socialist success story” narrative is both false and dangerous.

Narrative #2 – The Black Mirror Narrative

At least on Western social media, the “party fans” tend to have a tough time competing against the continuous flow of material coming from the anti-China crowd. Much of it is seemingly a rip-off of the 2011 British dystopian television series ‘Black Mirror’, often in the form of random video clips from China with fraudulent voiceovers. Viewers are told that China is a totalitarian hellscape tightly controlled and monitored by the omnipotent ‘CCP’, a kind of Borg-like entity with a godlike level of technical sophistication.

This entity controls and monitors everything, with all data fed real-time into a ‘social credit system’ which assigns a score to each person based on his everything he says, does and writes. According to some videos, fines for such sins as jaywalking are assessed instantaneously and deducted from the sinner’s digital wallet, with the sinner identified publicly on digital billboards.

For clarification, the ruling Communist Party of China, which is properly abbreviated as the CPC, does play an enormous role in governing China, but it is not the government itself. These details are however arguably irrelevant, since the whole point is to refuse to call the party and the government by their proper names and thus subtly insult them. This is analogous to the way the term ‘regime’ is used to mean a government the West doesn’t like, or ‘strongman’ to mean a president it’s not fond of.

This entity they call the CCP is traditionally depicted as overseeing an economy powered by slave labor, though in recent years perhaps somewhat less so, as this particular theme seems to have declined in popularity. Concentration camps are used to keep minorities such as the Uyghurs in line, millions of whom have been somehow “genocided”. The CCP also controls all businesses, plus in some cases various left-wing governments abroad, including even (according to some) the US Government and the US Democratic Party.

It furthermore masterminded the Covid pandemic, the flooding of world markets with cheap Chinese goods and the rollout of the toxic Western Covid vaccines.

And it’s on a quest to take over the world.

Whew. That’s a lot of work.

In all of this material, there is almost never mention of anything called the Chinese government, much less differentiation between local, provincial and national governments. Nor is there ever any doubt cast on the ability of this organization to live up to these truly herculean expectations.

Ironically this group seems to share a belief in the virtues of central planning with the party fans. It is never explained why this version of central planning is seemingly so successful, in contrast to the well-known miserable failures of previous attempts such as those of the Soviet Union or Maoist China. The subliminal message seems to be that the West needs to emulate this technocratic vision in order to be able to compete.

It’s often hard to avoid the impression that much of the attraction of this material is at heart a kind of projection, namely of the deepest fears of Western resistance circles regarding the development of their own society.

China’s ridiculous though not particularly totalitarian speech censorship policy

Though most of the above has little to do with reality, China’s current government DOES have some authoritarian policies, the most prominent of which is its unwritten speech censorship policy. It’s important to understand why it doesn’t fit in well with the Black Mirror narrative.

To be clear, we are talking here about restrictions on what people say and write, not about China’s policy of blocking Western platforms such as Google or Facebook, or government-aligned sites such as the BBC or the NY Times. Since the platform blockages are not difficult to circumvent, their primary purpose seems to be to prevent China’s Internet from depending on them. That is however a different topic.

The restrictions on speech (in Chinese: (内容监管 / 舆论管控 / 舆情控制) apply to statements posted online and especially to anything said at public events. To cite a few examples, in its current form the policy bans people from saying negative things about the economy or the stock market. It also apparently bans criticism of the party, the army and incredibly, even bans mentioning the president, explicitly or by inference. However, none of these restrictions have ever been published. In October 2022 we described this as a “zero-speech” policy, when precisely that was the case with regard to Beijing’s erstwhile zero-Covid policy. In today’s context, calling it a “zero-speech” policy would be an exaggeration, since most speech — including criticism of the status quo — is permitted. The problem is that it’s not always clear what is permitted and what isn’t. This uncertainty is in itself a big problem.

For casual critics sharing opinions online, the consequences of violating the above restrictions are rarely serious – usually just a deleted post, a view-restricted video, or in the case of independent media platforms a call from the censor demanding that something be removed. If repeated often, your account might be suspended for a week or two, or in extreme cases banned. On China’s top blogging platform Weibo bloggers are even held responsible for the content of comments. In other words, if you lack the time to actively police your comments, you had best close them completely.

By contrast, for professional journalists, comedians, and other public figures, the consequences can be much more serious. They face the danger of cancellation – i.e. a complete ban from domestic social media, significant fines and for particularly persistent repeat offenders, though it’s rare, imprisonment.

For example, in May 2023 the hugely successful Shanghai-based comedy studio Xiaoguo Culture (笑果文化) was fined a total of 14.7 million yuan (approximately US$2.1 million at the time) for a joke made by its star stand-up comic Li Haoshi. The joke was interpreted as mocking the army, and thanks to the fine, almost everyone in China got to hear it.

These days Western dissidents also face growing risks of censorship, fines, cancellation and even imprisonment; however, for material published in Chinese, the Western Internet remains a safe haven. The unsurprising result is that some of China’s leading journalists, intellectuals and businessmen have chosen to relocate abroad. This is by any measure a loss for China, even if they continue to create material while there.

Nonetheless there is an important context here: While the current censorship policy is absurd and clearly authoritarian, the reality is that it is not particularly totalitarian, in the sense that it isn’t very effective and doesn’t significantly impact most people’s lives. In particular, it doesn’t prevent information from circulating. Moreover, the restrictions don’t prevent people from publicly raising their voice about issues they see in the society around them, whether directly via the government’s 12345 hotline, or indirectly via social media. If complaints gain enough traction, government authorities still tend to react to them by attempting to resolve the issues. In fact, it’s fair to say that the Chinese government is significantly more responsive to citizen complaints than most of its Western counterparts.

Sure, the restrictions are annoying. They also represent a serious step backwards (倒退) for society and the rule of law. But do they accomplish anything other than crippling the development of independent media and driving serious journalists abroad? Content which people want to communicate gets shared anyway, using code words, by sending material to others as private messages, or by using foreign platforms such as YouTube.

Just to cite one example, during the 2022 Shanghai lockdown, one protest video was shared an estimated 400 million times before it was finally banned from private messages. And it was only one of countless others which achieved mass distribution during the Covid years.

Though its impact on individual journalists and public figures is huge, in terms of the society as a whole, the most significant impact of this cat and mouse game is not to prevent the public from obtaining information. Rather it (a) makes the government look weak in the 40+ age segment of people paying attention, (b) impedes market research, (c) inhibits economic development and (d) severely impacts the government’s own ability to find out what’s going on.

There’s some karma at work there.

Narrative #3 – The China Collapse Narrative

Like the Black Mirror Narrative promoters, the Collapse Narrative advocates also refer to the Chinese government as the ‘CCP’. That’s where the similarities end, however.

For those pushing this narrative, instead of superhuman, the CCP is in reality a master illusionist, overseeing a huge house of cards destined to eventually collapse. This CCP iteration completely lacks original technology, since everything was stolen from the West.

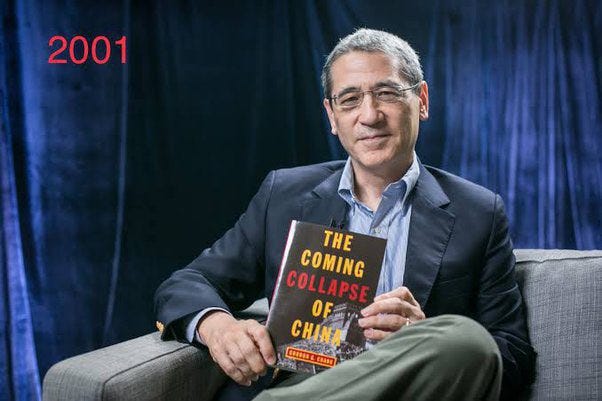

This narrative was first rolled out in 2001 by author Gordon Chang with his book “The Coming Collapse of China”.

23 years later we’re still waiting.

Since then for some Western media these announcements have practically become an annual tradition.

Skipping over a long list of doomsday promoters in the intervening years, today perhaps the most prominent dean of the collapse school is Peter Zeihan, a former employee of CIA-contractor Stratfor.

According to Zeihan, “we’re looking at the end of China as a political entity within a decade or two.” Zeihan has been delivering similar predictions since 2010, justifying this with China’s shrinking population.

As we explained in our August 2023 analysis of the Chinese economy, China does have some significant economic problems, many of them caused by the current government’s addiction to deficit spending, money printing, interventionism plus its recurring dabbling in central planning. But problems are not a collapse. Poor policy choices doubtless impact economic efficiency and hamper economic development. But unless market mechanisms are completely suspended – basically an impossibility – poor policy decisions and interventionism lead not to collapse, but rather to lower growth rates and sluggish recoveries. This is exactly what we are seeing.

To put it another way, though interventionism and poor policy choices inevitably impede economic growth and slow down recoveries, China’s enormous existing base of productive capital continues to generate its own momentum.

As to Zeihan’s main pitch, there is absolutely no basis for his claim that a shrinking population creates an economic problem. It’s true that China’s labor costs have risen dramatically over the past 10 years, but there is no evidence whatsoever that higher labor costs have impacted China’s competitiveness. On the contrary: High wages are highly correlated with industrial dominance. Nor is there any issue with supporting a higher percentage of retirees in an a highly automated economy which is the world’s leading producer and user of industrial robots.

The collapse enthusiasts aren’t very consistent however. If wages are falling, apparently that’s also an indication of an ongoing or upcoming collapse:

Either way, collapse is imminent.

Narrative #4 – The “CCP Bad” Narrative

Finally, there are lots of posts which seem to generally communicate the diffuse idea that the ‘CCP’ is bad, or that China is backward, or that China somehow is communist but yet not communist enough. It’s hard to know what to say to people like this.

Take this one for instance:

This poster is claiming on the one hand that China is communist, and then on the other that China isn’t communist enough for him, because it doesn’t have free medical care.

Or this one mocking an Internet streamer who forgot to turn on the beauty filter. Some obvious questions: Why is this blogger a “communist”? And what does this have to do with the “CCP”?

In response we get the collapse narrative (“smoke and mirrors”).

Or this one implying that Chinese are dirty:

Or this one complaining about an “evil alliance” which the CCP allegedly has with various other enemies of the day:

Or this one attacking anyone considered to be insufficiently anti-China to satisfy the poster’s requirements:

In the third post above, this guy’s “claim” seems to be that @RealJermWarfare was “fawning over [Chinese] government provisions” – whatever that means. What is a government provision, and, ahem, which ones did Jerm “fawn over”? Where are we advocating for the “0.1%”? And speaking of incoherency, what is a “biosecurity techno state”?

Perhaps not coincidentally, the kind of jargon one encounters in such posts is often reminiscent of empty Communist party slogans. In that light, one should not be surprised that it’s rare for any real discussion to take place.

In case we missed anything, this post kind of sums up the entire category:

Given all this diffuse negativity, it should also not surprise us that this kind of result is widespread — China is bad but they don’t know why.

The real China is not black and white

Amid this flood of incoherent and cartoonish posts, many Westerners inevitably end up completely forgetting a third possibility, namely that China might just be a country like any other market-based economy, with some virtues and some vices, some things which work well, and others which are annoying. Some dumb policies, some good ones. One can be critical about the dumb policies and still appreciate the good ones. It’s that simple.

Did we miss one or more of the popular narratives on offer? If so, let us know in the comments.

This is the best primer on China and how the Chinese economy works I’ve ever read. The point you make about China being essentially a federated system (much like the US) is something Westerns need to hear.

I hope you are able to promote this piece.

First rate!

Thanks for the long post! Perhaps China is like the EU, a regional power that sits on top of a tree of more local governments.