China’s Economy – The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (Part 1)

Keynesian policies and interventionism are the root of China's economic woes

View from China with an Austrian School of Economics Perspective

This two-part article has been a long time in the making. In the West there is of course never a shortage of doomsday articles and videos on China. Sometimes they do reflect real problems, but they rarely offer a balanced view. The reality is that the Chinese economy has accumulated some serious structural problems caused by the Keynesian policies adopted after 2008. However, these need to be seen in the context of China’s vast private sector-powered economy, its enormous manufacturing capacity and its lynchpin role in the worldwide industrial supply chain.

Assessments about China’s economy and its prospects vary widely, to some extent in China, but mostly in the West. Some of the most popular questions:

Is China’s economy doing well? Or poorly? Is it all just a “big bubble” about to collapse, as Gordon Chang and his fan club has been claiming for the past 20 years?

Is the economy in reality far smaller than claimed, because the “CCP” (the term used by the anti-China crowd in the West to refer to the Chinese government) is faking the numbers?

Is China’s economy based on “slave labor”, with most of the population living in desperate poverty while a small elite enjoys a life of luxury?

Are the Chinese “saving too much” and “consuming too little” as the Keynesians claim?

If not immediately, is collapse in the medium term inevitable, as Peter Zeihan claims, because China cannot possibly adapt to a smaller population?

In Part 1 we’ll look at these questions. Then in Part 2 we’ll look at how China became the world’s leading manufacturer and what some of the critical factors are which give China its competitive advantage.

To put the above questions into the appropriate context, readers who erroneously believe that China has a centrally planned economy, or that all Chinese companies are controlled by the “CCP” should first take a look at Myths #1 and #7 in our two-part “Top Ten Myths about China” series. In fact, not only is the bulk of the Chinese economy NOT the result of central planning, but the government’s hands-off approach in the period from approximately 1992 to 2008 was what made China into the world’s largest economy. It also led many of China’s super competitive private sector companies to dominate their industries worldwide.

That does not however mean that the Chinese ruling establishment has given up on central planning. On the contrary, especially in the past five years, the idea that the proper role of government is to guide economic development has once again become fashionable. On the ground, this has translated into a significant expansion of the regulatory framework (= the “regulatory state”), unpredictable interventionism, selective persecution, heavy fines and preferential policies for favored industries.

In this article we will look at the substantial evidence which links these policies with China’s current economic malaise. But before we do this, we need to set the stage.

How big (or small) is China’s economy?

In a recent piece we published on June 29th, we analyzed the latest estimates of worldwide GDP published by the IMF in 2023 for the world’s major economies, producing a ranking of top economies based on their total Productive GDP, i.e. how much stuff they make. We then compared these with several other indicators of economic activity, such as electricity usage or passenger car registrations. While GDP numbers must be taken as estimates at best, in this case the other indicators do seem to support the IMF’s GDP numbers.

According to these 2023 IMF estimates, if we use purchasing power parity to value the products produced, China now produces approximately three times as much stuff as the United States. It also produces more than the United States, the EU and Japan combined. This huge discrepancy is a pretty big deal if you consider that prior to being surpassed by China, the United States was the world’s leading manufacturer for over 100 years.

This is of course only an approximation, but its basic truth will not surprise anyone who has visited a Tesco or Walmart in the West recently.

Those who are still skeptical might want to take a look at SL Kanthan’s excellent Youtube video on the topic. It’s entitled “Debunking Conspiracy Theories about China’s GDP.” In this video, among other things he challenges the idea that the Chinese government has an interest in overstating the size of its economy. He points that, on the contrary, given the extreme fear in the West of being economically overtaken by China, the Chinese government has a geopolitical interest in understating the size of its economy.

Note that here we are talking about absolute numbers, not about growth numbers. It is possible for government statisticians to systematically understate the overall size of the economy while simultaneously exaggerating and/or smoothing out annual growth numbers. The former number (the size of the economy) is more relevant to the foreign audience, while the latter is what gets all the attention domestically.

This is in fact the most probable scenario.

With regard to the total size of the Chinese economy, the fear in the West is real and exists for a reason.

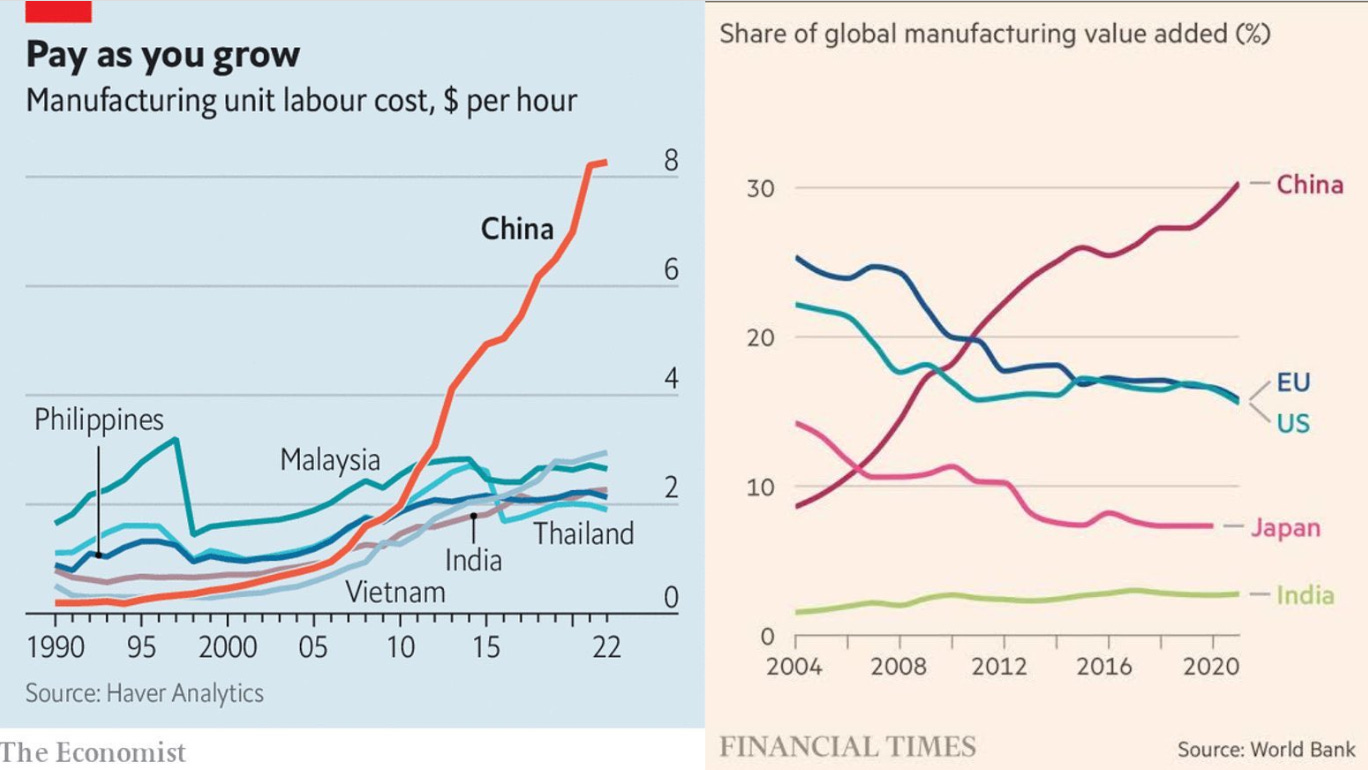

Note that the production of goods (aka “stuff”) is a much broader definition that what is defined as “manufacturing”. Depending on how narrowly manufacturing is defined, the numbers will vary widely. For example, in a 2018 article the Brookings Institute claimed that in 2015 China had only a 20% share of worldwide manufacturing with total production valued at $2 trillion. By contrast, a recent article by the UK’s Financial Times claims that China already had a 25% market share by that point. And of course there a huge gap between this number and the $16 trillion cited in the above table for the production of “goods” 8 years later.

This recent comparison of manufacturing output published by the FT in the above mentioned article shows a China to USA ratio of around 2:1 instead of the 3:1 ratio we saw in the Productive GDP ranking. What is interesting about this graph is that it shows China surpassing the USA as recently in 2009. The speed with which China has since then left the USA behind in the dust is almost unprecedented in world history.

This is despite the fact that real wages in China’s manufacturing sector exploded during the same period, rising over 4x. And it is despite the fact that the Chinese government went on a money printing spree during this same period, a policy which placed the manufacturing sector at a substantial disadvantage vis-à-vis economic sectors closer to the printing press.

The perhaps unsurprising response to this on the part of the United States has been protectionism and an attempt to cut off China from key technologies. History hints that such strategies are unlikely to work.

That said, the same cannot however be said of self-immolation. Today China’s home-made confidence crisis is having a far more acute impact than any amount of US protectionism ever could. More on that a bit later.

The Cheap Labor Myth

When the United States took over the position of the world’s leading industrial power from the UK in the late nineteenth century, it was not low wages which made this possible. In the fact, at the time it allegedly had the world’s highest per capita GDP. The same is true of the world’s other two leading exporters today: Germany and Japan. Both have higher wage costs than almost all of the countries which they export to.

Clearly low wages are not correlated with industrial dominance. On the contrary, industrial dominance is much more likely correlated with higher wages, because this dominance gives manufacturers located in these countries a built-in competitive advantage.

China’s experience only confirms this. If we look at China’s numbers for wages and production since 2000, we can see wage levels steadily rising in tandem with China’s rising share of worldwide manufacturing. Average wages rose 10-fold over the past two decades, to the point where they are now nearly four times the levels in nearby Southeast Asian countries. During that same period, China’s share of global manufacturing grew from 6% to 30% and China’s share of global exports grew from 2% to 15%.

In his outstanding June 2023 post on the importance of manufacturing SL Kanthan writes on this point:

Even in labor-intensive manufacturing, the success of an industry depends on more than cheap labor. Take textile production, which conjures up images of sweatshops. However, China leads the world and exports 7 times as much as India, even though related wages in China are 4 times higher than in India.

As to claims that China’s manufacturing success is based on slaves toiling away assembling tents, cups, watches, shoelaces and lawnmowers, as we have seen, that is sheer fantasy. Slavery is not the secret of industrial success.

Is China saving too much?

Keynesians can often be heard saying that as countries become wealthier, they need to invest less and consume more. To use Keynesian phraseology, there is a shortage of “aggregate demand”.

In times past, such statements were peppered throughout critical articles in the Western press on China’s economy. In the past few years such claims seemed to have been mostly drowned out by the doomsday / collapse crowd, but the current crisis has brought them back into print.

One example is this recent video by Beijing University professor Michael Pettis.

Another is the recent interview of a member of one of the PBoC’s advisory councils, the well-known economist Cài Fǎng (蔡昉). It was posted late Monday on a social media account of the China Finance 40 Forum, an economic think tank. In March 2023 Cai had argued for a “helicopter drop” of 4 trillion yuan to boost consumption, but this time around he avoided naming numbers. Now he advocates giving urban resident status to migrant workers, so that they can gain better access to the government benefits connected to this status.

It is not clear why he believes that this particular type of government spending is somehow more beneficial than, say, just arranging more banquets for high level officials, or buying more luxury vehicles.

In any case, it this true? Would more spending and less saving be “better”?

Uh, no. Not unless Michael Pettis, Cai Fang and their fellow Keynesians want China to stagnate and eventually become poor once again.

The United States has tested this strategy for several decades, with well-known results: stagnating wages and widespread impoverishment of society.

This result should not be surprising, since this Keynesian concept defies basic economic logic, namely: Production = Consumption + Investment + Commodities Stockpiling, where Investment = Savings. Since there is typically only limited space for stockpiling, for the most part you can either consume production or invest it1. To put it another way, you either make consumption goods or you make production goods. If you consume more, you save and invest less in the future. This means less wealth for you in the future. Building a better future means getting those savings in the hands of the smartest investors, not the people who want to use it to buy make-up or spend more time vacationing in Sanya.

But what if no-one wants to buy the existing ‘production’? If not enough people want to buy the goods and services on offer, for example because the real estate developers are on a much needed diet, then the people previously employed in the construction industry will have to find something more useful to do, something for which there is an actual demand. The job of a functioning market is to figure out what these things are. This transition may not be easy for many of the affected workers previously employed in shrinking industries, but such “adjustment pain” is a well-known and unavoidable consequence of this kind of asset price bubble.

As we will discuss later, those asset price bubbles are the consequence of government money printing.

Is China going to collapse for demographic reasons?

This is the Peter Zeihan thesis which has been heavily promoted in the West over the past year.

Uh, no.

Given China’s low birth rate, it is certainly possible that China’s population may eventually shrink. The same is true of many countries. Zeihan claims this is tantamount to a catastrophe, but he supplies no evidence to support this claim. Shrinking and aging populations typically lead to higher wages, but as we have seen above, there is no issue with that. On the contrary. A highly automated modern capitalist economy such as China’s is not dependent on cheap labor and produces enormous surpluses. So at least in terms of material goods, supplying the needs of a large number of retirees is not an issue.

As in all societies, there is always the conundrum of how to deal with retirees without savings or children to support them. But this problem is one faced by all societies, not just China. For most families, the standard three generation household is the solution.

What’s the current state of China’s economy?

The short answer is…. ugly. While the Covid lockdowns were literally the lead bar which broke the camel’s back, the problems started long before 2020, and thus the reasons for China’s quandary are neither superficial nor transitory.

And no, this is not doomsday, but the problems are serious.

To understand why, we have to look back at what happened over the past 15 years.

During that period, China has gone through huge changes. While the private sector continued to expand and modernize, in particular building the largest e-commerce infrastructure in the world, the Chinese government went on a spending spree. It abandoned its previous policies of light regulation, minimalist government and balanced budgets. Government spending almost tripled, going from ~11% of GDP in 1995 to ~31% in 2022, 7.4% of which was deficit spending2. At the same time and especially in recent years, large-scale unpredictable government interventions multiplied. Some of the better known examples include its takedown of the crypto industry in 2017, its takedown of the private education industry in 2021 and the multi-billion dollar fines levied on several large foreign-listed companies like Alibaba, Tencent and Meituan. If these were isolated cases, this might be less of an issue. But they are not.

Though each country has its own particularities, generally speaking, China is not particularly unique; countless others went through similar processes as they became wealthier: both government spending and the regulatory load expanded dramatically.

What in China’s case is however somewhat unique is the extreme unpredictability and in many cases severity of China’s government interventions. This arguably erratic behavior represents a substantial departure from China’s previous long standing track record of reliably predictable government.

Most visibly the government invested massively in physical infrastructure, not just in the major cities but literally all across the country. The result is what is now in many respects the world’s most advanced physical transportation network, with more kilometers of motorways, subways and high-speed train lines than the entire rest of the world combined. Thousands of bridges and tunnels were built, all over China. These days even ordinary roads are for the most part (though there are still exceptions!!) well paved and maintained. And though there have of course been some quality issues, the quality standards for, say, a train track, are far simpler to measure than those for a school. Moreover, if a tunnel or a bridge collapses, the contractor is likely to be held responsible. As a result, for the most part the roads, bridges, tunnels, trains and train tracks are of reasonable quality.

In addition to roads and train lines, lots of buildings were also built – principally schools, hospitals and markets. (Prior to 2015 scores of imposing government administration offices were also built, but in 2015 such spending was formally banned.) Besides buildings, what also gets built are artificial lakes, fountains, public squares and industrial zones. In the more rural areas many of these markets and industrial zones remain empty. For the officials in charge, such projects provide both corruption opportunities and brownie points for the completion of “successful” projects.

Needless to say, it is easier to build schools and hospitals than it is to improve the real quality of education and health care on offer. This is the problem with government-led investment – the real results are not what counts.

Shortcomings aside, violent crime in most major cities is now almost non-existent, wages have risen dramatically, and the standard of living has risen everywhere, even in remote areas. Just as a point of comparison, even in border provinces such as Xinjiang and Yunnan, average income levels have risen to levels exceeding those of most other countries in Asia.

The list of superlatives is long and admittedly, in the long term much of this investment may well end up generating a positive return on investment. At a minimum it has a better RoI than manufacturing a bunch of weapons and ammunition. Nonetheless, as we have written on multiple occasions in the past (in particular here), massive deficit spending on this scale in combination with a rapidly expanding money supply has a number of problematic consequences - consequences which are not minor.

One of the most obvious of those consequences was the real estate price bubble. Investment (and thus savings) flowed into real estate and other “hot” sectors.

A less obvious consequence was that the industrial sector got the short end of the stick. This meant that companies investing in new plants found it increasingly difficult to get uncollateralized loans. In other words, investment which otherwise would have landed in productive sectors, for example making stuff, went to non-productive sectors like real estate instead.

Initially, to an extent the wealth effect generated by the real estate price bubble masked the general malaise affecting the industrial sector. Now that the bubble seems to have definitively burst, that malaise has become more visible.

In years past, on several occasions the bubble seemed to be on the verge of bursting; yet each time another round of fresh money managed to prop things up. This time around, by contrast, after three years of unprecedentedly massive interventions in the economy, it seems that trick is no longer working. The result has been sharp price declines in many (though not all) areas, with third-tier cities and sky high-priced prestige condominiums especially hard hit.

While this decline in real estate prices is probably the most glaring symptom of the economic crisis China is facing in 2023, the real problem is a general lack of business confidence on the part of the private sector. Confidence is lower than it has been in decades. The last time business confidence was this low was in 2008, but that was caused by an external shock and did not last. Ironically one of the terms used to describe this reluctance to invest is “tǎngpíng” (躺平), i.e. lying flat, a term used during the final months of China’s zero-Covid policy to disparage critics of the government’s hopeless containment efforts.

From the government’s perspective, the crisis shows up as a drastic reduction in tax receipts. Apparently the numbers are actually even worse than during the lockdown year 2022. Of course the national government can just print up a bunch more money and use that to bail out the struggling local governments, and in fact, that is very likely precisely what they are doing. Nonetheless, arguably to their credit, they seem quite reluctant to do this. The alarm over the massive gap between expenditures and receipts has now become so severe, that according to some reports, in many areas government employees are being asked to repay bonuses they received in the past few years to help plug the gaping hole in the government budget.

What brought us to this point?

While it is impossible to provide one single answer, some of the reasons are obvious.

Here are some of them in bullet point form:

Massive government spending re-orienting large sectors of the economy to be dependent on government spending for infrastructure projects. In other words, instead of flexible consumer demand driving the economy, as it did back in 1995 when government spending amounted to only 11% of GDP, the economy is now addicted to the massive deficit spending which kicked off in 2008. This deficit spending has been at over 10% per annum for many years now, with the gap being plugged using the printing press.

A focus on enforcing regulations to the letter, especially after 2013, regardless of how unrealistic, petty or damaging they might be. This led for example to the closing down of countless street markets, because most vendors lacked both business licenses and a fixed address. Crackdowns on illegal additions to houses are another example. In cities it’s typically not possible to apply for a building permit and in rural areas it’s difficult to get them approved. Prior to 2020 (when they realized they had more important things to do) local governments began to purchase and send out drones to check for illegal additions visible from the air. If discovered, the owners can be fined and/or forced to demolish them. And perhaps even more attractively, local responsible officials can collect a kickback for turning a blind eye. In other words, effectively this amounts to a hidden tax going to corrupt officials. Almost all of these regulations are destructive rather than constructive.

New laws such as the 2008 Labor Law imposing higher costs and mandating all sorts of inflexibilities which complicate business management, for example by imposing a huge financial burden on companies with pregnant employees, forcing their HR departments to discriminate against young childless female employees.

A hostile attitude towards many of China’s top-performing companies, leading to repeated massive fines and in some cases (e.g. Alibaba) the displacement of their management. How can companies be expected to innovate and invest when they are constantly faced with the danger of such predatory behavior on the part of the state?

Punishing private sector success. Think of the canceling faced by a number of well-known movie stars and public figures like Wei Ya or the treatment suffered by Alibaba’s founder Jack Ma.

Discouraging private sector organizations and private initiative, such as private charities, replacing them by ineffective government-run ones.

Regime uncertainty. Large-scale unpredictable interventionism, particularly in the Covid years, leading to the destruction of countless businesses. A prime example of this was the takedown of the private education industry in 2021. Rarely was any compensation ever paid.

A dysfunctional public health insurance program funding a bloated and corrupt medical establishment. We will take a look at this in an upcoming article.

A seemingly callous attitude on the part of the government towards the victims of its interventionism. The recent flooding of Zhuozhou south of Beijing is a good case in point. The city was completed flooded by destroying dikes north of the city – in other words due to a decision by the government to “sacrifice” Zhuozhou to save Beijing. The government has offered 70% compensation for the damage caused. While this is arguably better than the 0% compensation offered to the victims of the government’s Covid lockdowns, it’s hardly confidence-inspiring.

The government’s increasingly farcical zero-speech policy, which this year has progressed to the point where all public statements about the economy perceived as ‘negative’ are banned. To understand what a radical departure from previous practice this represents, until approximately 10 years ago, China had very few restrictions on free speech. Even sensitive historical topics could be openly discussed and criticism of government was nothing special, not only in public forums, but also in the official government-owned print media outlets, many of which retained substantial latitude to adopt their own editorial positions. This liberal policy came to a dramatic and abrupt end in January 2013 with the widely publicized conflict between the editorial staff of the liberal Southern Weekly (南方周末) and the Guangdong government’s propaganda department. For those unfamiliar with the story, it’s one worth reading.

To be sure, one of the most important reasons for China’s success is that the government does not always get what it wants. China has long-standing traditions of disobedience and resistance against what are perceived to be illegitimate or stupid government policies, and this resistance often succeeds. While the Guangdong government did ultimately prevail in the Southern Weekly case, enforcement was made far simpler by virtue of the fact that the Southern Weekly was and is a state-run company. When individuals or non-state-owned companies are the targets, enforcement tends to be more difficult.

One of the more unforgettable examples of this in recent years was the ill-considered rule announced one December 31st prohibiting car drivers from driving through yellow lights. Clearly the bureaucrat who formulated the rule did not understand the point of the yellow light.

The rule was abandoned after a few hours of chaos and accidents.

Government attempts to restrict and/or expose the cash economy are another area where the government has made little progress. For example, the central government has on multiple occasions announced regulations requiring personal bank account holders to provide a reason when withdrawing more than 50,000 yuan in cash. None of these efforts were implemented due to resistance on the ground.

Such incidents do much to make the government look ridiculous and incompetent.

Nonetheless, many rules do end up taking affect, and just as in the West, each additional rule further complicates life and in many cases blunts individual initiative.

Moreover, also to its credit, the Chinese government has made no change to its long-standing resolute and explicit rejection of the Western welfare state – what they term the ‘welfarism trap’ (福利主义的陷阱). In line with this, China still has no meaningful system of transfer payments to consumers other than the old-age pension scheme. The message is clear – everyone needs to contribute. As CPC Spokesman Han Wenxiu put it in an August 2021 press conference, “我们… 不能养懒汉” - i.e. we can't afford to support lazy people3.

Nonetheless, despite these caveats, it is not inaccurate to say that China has moved from the night watchman approach it was following in the mid-1990s to what is in some (though not all4) ways the standard interventionist “big government” model which has led much of the West to the morass it finds itself in today.

While this in no way implies that Gordon Chang’s dreams of seeing China ‘collapse’ are likely to happen any time soon, it does hint that China cannot simply continue with “more of the same”.

Will the resulting crisis be sufficient to undermine China’s worldwide industrial leadership and lead to a trend reversal? Only time will tell, but as we will discuss in Part 2, the process of production is an almost infinitely complex interlocking system. Once supply chains and the infrastructure of production are in place, it takes a long time to destroy them, and in particular to relocate manufacturing supply chains elsewhere. This is doubly so the case when such a large part of the world’s supply chains is centered in one country. So despite the severity of the issues, decline is not inevitable. Moreover, no third party is available to bail China out, so it will have to find a solution on its own.

Fixing the leak

Without going into great detail, at a minimum there are at least a number of signs that the Chinese government has realized that real change is needed.

For example, there is the rumor that the government has managed to lure Jack Ma back to Hangzhou.

There have also been repeated declarations that the witch hunt against China’s leading “中概股” companies listed on the Hong Kong and New York stock exchanges is over.

And perhaps most notably, the Chinese government recently released two official statements, one declaring its support for the domestic private sector, and the other declaring its determination to improve conditions for foreign investors.

These are all symbolic acknowledgements of the need for a break with the past. Such symbolism is meaningful. Nonetheless, they are hardly radical steps, and without radical steps, restoring investor confidence is not going to happen overnight. Moreover, with their mentions of preferential policies for this group and that, the above two announcements make amply clear that the government’s renewed infatuation with central planning remains unwavering.

While ordinary investors may not see this problem as clearly as we do, most do have a sense that what the government has offered thus far are mostly platitudes. If systemic changes are in the works, it’s not apparent.

The highly publicized crackdown on corruption in the state-run hospital network in progress this week is an apt and glaring case in point. Sure, a few corrupt doctors and hospital administrators get arrested and some piles of cash get confiscated, but is any thought given to the monopolistic structures which make all this corruption possible? If there is, it is not being publicized.

Crackdown #43909 and hundreds of new rules are not going to change anything fundamental. Instead, they just further stifle innovation and investment. Just as in the education industry, today there are already so many rules and restrictions in the medical sector that most real growth is forced into the black and grey markets. These have flourished over the past few years despite all the difficulties involved in setting up and maintaining such parallel structures. Just to cite one example, over the past few years, IV treatments with stem cells have once again become available to ordinary citizens. For over a decade only high level party officials had access to such treatments; everyone else had to go abroad. However, over the past few years a number of black market services offering stem cell treatment have emerged, with – thanks to competition – prices falling as low as 20,000 yuan for 100 million cells. Now these are all on hold while waiting for the dust to settle. Is this kind of crackdown going to inspire business confidence or increase economic activity? The answer is obvious.

What would create confidence would be the liberation of the medical industry from the chains that prevent privately owned pharmacies, testing centers and clinics from competing with the public hospitals on an even playing field. At this point no-one has any reason to believe that something of this sort is likely to happen.

No doubt China’s economy will eventually revive without such fundamental change, but this revival will inevitably be far more timid and sluggish than it could be if real change were permitted: namely a return to market-driven structures.

Markets often have to first hit rock bottom before a real lasting trend reversal can start. The same principle seems to also apply to economic policies. As the United States has shown, the road down to that turning point can sometimes be a long drawn-out one. It takes a long time to fritter away generations of accumulated capital. We can only hope that at some point the leadership in Beijing finally realizes that the US regulatory state is a disastrous role model.

Follow us on Twitter @AustrianChina.

This is a simplification of the actual formula, which needs to add in imports and exports. Production can also be sent abroad in the form of exports, or imported via imports.

Sources: GDP https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1755246560915267705; government income and expenditures: http://gks.mof.gov.cn/tongjishuju/202301/t20230130_3864368.htm. 2022 official GDP was 121.0207 trillion, versus spending of 37.1192 trillion (26.0609 regular budget + 11.0583 from special funds). As a percentage of GDP, the number is however down from almost 36% in 2020.

While the principle may be solid, in reality it is bit by bit being undermined by the massive losses being incurred by China’s rapidly expanding public health insurance scheme. This is ultimately also a kind of welfare.

Besides its minimalist welfare system, effective tax rates for many businesses still remain fairly low. There is also no mass surveillance system monitoring financial transactions like the ones in place in almost all Western countries.

yellow lights ban is hilarious - we don't want you to choose - you will be told to stop or go - no exceptions - love that. Even if someone knew that this was going to result in chaos - they were too scared to tell the boss - which i think is the root of nearly everything you mention - constructive criticism is not even a term they know.

Following your guide, and 15 days wait time to change my "Real Name", I managed to get a Dutch credit card into WeChat Pay! Thanks.

Dutch welfare is the opposite of "subsidizing the lazy". It is brutally punishing: think unannounced inspections of your home, a public servant checking your bank statements, constant uncertainty due to changing rules. Welfare means replacing an extended family safety net with exploitation.