Lessons to be learned from China’s massive Covid control experiment

Except at the crematoria and hospitals, Covid-19 is slipping into the past.

View from China with an Austrian School of Economics Perspective

As of January 10th, Chinese borders are now officially re-opened. In theory, proof of a negative Covid test is required to get on board your plane, but that’s it. Tourist visas still remain suspended and still cannot be applied for, but all other visa types are now available as long as you aren’t Korean. Issuance of visas to Japanese nationals has now resumed.

At the same time, aside from all the dead small businesses and restaurants, life in most cities has for the most part returned to normal. In both cities and most of China’s densely populated rural areas, Covid-19 swept through by mid-December at the latest, with most people having recovered by the end of the month. Until mid-January when things began winding down for the Lunar New Year holiday, parking lots were full again. Deliveries were arriving promptly, while offices and factories were once again back to work.

There were of course some exceptions, however: in particular, quite a few elderly did not survive their struggle with Omicron, and some still remain in intensive care. The government released a claim that approximately 60,000 people had died of Covid-19 during the peak of infections, but in light of leaked death statistics from smaller areas and exceptional measures being taken to reduce the crematoria backlog, this seems rather dubious. More on that later.

Masking is still at high levels, but aside from a few places such as hospital entrances and the subway, there is no longer any checking. Health codes are not checked anywhere; however, the Alipay and Wechat mini-apps which used to provide access to them have changed names. They are now called something like “Medicine & Health” (医疗健康) instead of Health Code (健康码). The health code still exists but all the PCR test records are gone.

So more or less chapter closed. Yet after almost three years of lockdowns, deportations and endless testing, there is much to learnt from what happened. With so much data available and so many people involved, this is absolutely certain. Let’s take a look at a few of them.

(1) Masks. Masks clearly have no measurable effect in terms of protecting their wearers from getting infected with Omicron. It doesn’t matter what masks are being used (N95, surgical, whatever). Nor does it matter how much antiseptic gets sprayed. Even the most diligent mask wearers were infected, just like all the rest. This was true in the spring during the Shanghai outbreak, and remains true today. This is an unpopular truth in China.

(2) Natural immunity. Previous infections with Omicron seem to either protect against re-infection or protect against display of symptoms. A survey of 40 people in Shanghai infected in the spring showed that 36 did not get infected this time, while 4 did test positive for a day or two, but exhibited no symptoms.

(3) Accuracy of PCR test-based diagnoses. Almost all people who tested positive for Covid-19 for the first time in December exhibited clear symptoms of illness. (“Tested” here refers to a PCR test for two genetic snippets using a cycle threshold of 40.) This is common knowledge in China; however, statistics on this were never released by the national health commission, perhaps because it completely contradicts their prior narrative.

According to that prior narrative, the vast majority (80-90%) of cases were ‘asymptomatic’. As we explained in earlier articles, this claim was however based on an absurdly narrow definition of what were considered to be ‘symptoms’, and the authorities merely ended up making themselves look foolish as soon as they abandoned their zero-Covid policy. Were China’s senior leaders duped by their own propaganda? So it would seem.

There are however statistics from some areas of China, one of those being Ordos city. According to the Ordos city health department, only 1.75% out of 16,000 cases examined exhibited no symptoms. 79% percentage ran a fever; 69% reported experiencing headaches; 61% reported having a sore throat. In other words, statistically speaking the correlation with the PCR test results was extremely high, a result some Western observers find very difficult to accept. Anecdotal reports from other areas are quite similar, so there is no reason to assume that this data set is special in any way. We’ll take a deeper look at this in the next section.

(4) Accuracy and usefulness of antigen tests. While we are unaware of any public data regarding the accuracy of the antigen tests, extensive anecdotal data seems to indicate a fairly high degree of correlation with the PCR test results, albeit with somewhat different timing. The antigen test seems to be a bit slower to produce a positive result than the PCR test. The antigen test nonetheless has a function which the PCR test lacks – the thickness of the ‘infected’ (T) line roughly reflects the stage of the infection. In other words, towards the end of the illness cycle, the line becomes progressively fainter. This can be very handy.

Note that a positive antigen test does NOT necessarily imply anything about the severity of the symptoms. This is especially obvious in the case of people with a history of previous infection. They may test positive for several days without having any symptoms at all. The same is true of people protected by the use of hydroxychloroquine plus zinc as a prophylactic. They can be infected yet remain either symptom-free or with very minimal symptoms. This emphasizes that crucial insight that the existence or lack of natural immunity, among other factors must absolutely be taken into account when looking for correlations between test results and actual illness.

(5) Death rates from Omicron. According to the China CDC, 59,937 Chinese died of Covid-19 during the period from December 8th to January 12th , i.e. in a little over a month.

These numbers do not seem credible. Since on average approximately 30,000 people die every day in China, even if these were ALL additional excess deaths, this would be equivalent to an increase of only ~5.7%. This number would be significant, but not enough to explain the substantial backlogs in the crematoria of many cities.

Though to our knowledge this has never been publicly acknowledged, in Shanghai the cremation backlog is so severe that as a rule, multiple corpses are now being cremated together, thus commingling the ashes. “Upgrading” to private cremation apparently costs around 20,000 yuan extra – if you know the right people.

One explanation for this apparent fudging is that deaths are allegedly not attributed to Covid-19 if the deceased did not test positive immediately prior to death. True or not, these official numbers do not seem meaningful.

What we do have however are leaked numbers for the 65+ age category from a Beijing-based government institute. These numbers show a 2.1% death rate out of a total of approximately 1,000 retirees. This is quite a substantial number and far in excess of numbers the equivalent age group in any Western country.

By contrast, anecdotal evidence would seem to indicate that Covid-related deaths among those aged 50 and under are extremely rare. Hard numbers however remain elusive and may have to await excess death statistics broken down by age group.

(6) Lockdowns CAN work, at least temporarily. This is another conclusion which conflicts with the favored narrative in certain Western circles. It’s a fact that Western lockdowns were for the most part unsuccessful in preventing transmission or containing outbreaks. The approaches which Chinese authorities used in the first two years were also often less than successful at stopping transmission.

These failures are often interpreted to mean that lockdowns CANNOT work, a conclusion which does not make logical sense.

In fact, Omicron’s extremely high level of infectiousness provided ideal conditions to both study transmission paths and to rate the effectiveness of various measures designed to prevent such transmission. Essentially Omicron amounted to a trial by fire, relentlessly exposing every weakness of the various control strategies attempted.

By approximately mid-May of 2022 during the final weeks of the two-month long Shanghai lockdown, the health authorities seem to have finally figured it out. Of course on a national level in the end they also failed abysmally to contain Omicron; however, their temporary success in several cities nonetheless offers invaluable insight into how transmission actually takes place. This is a fact regardless of whether or not it was deemed to have been “worth it.”

Edit: It should be noted that it is likely impossible to separate out the effects of the sporadic lockdowns from the other measures taken at the same time - namely, mass comprehensive testing in combination with the quarantining of all cases and close contacts. Objectively speaking we can only state that - at an astronomical cost - in the aggregate the measures adopted enabled China to delay the Omicron tidal wave by approximately one year.

How the “PCR tests” are currently interpreted in China

As most people all around the industrialized world are doubtless aware, so-called PCR tests began to be heavily used all around the world around April of 2020 to identify people infected with variants of the Covid-19 virus. The purpose of the PCR process is to amplify certain genetic snippets by replicating them so that they become detectable.

At the time, critics pointed out that with a sufficient number of cycles, genetic snippets could “appear” without any correlation to actual illness. Some critics went as far as claiming that replication beyond a certain number of cycles (25? 30? 35?) led to useless results.

China of course accumulated more data than any other country by several orders of magnitude, and thus had ample opportunity to look for meaningful correlations. In the form in which it is typically used today in China for Covid-19, the PCR tests target two genetic snippets, producing a “cycle number” result for each one. In other words, the results simply state that x number of cycles were necessary to make that particular genetic snippet detectable.

The cycle threshold in China for people lacking a record of infection in the previous 6 months is 40 cycles for both snippets. For the others (those previously infected) a threshold limit of 35 is applied.

The key thing to realize here is that Chinese health authorities performed probably over one hundred billion such tests. Of these 100+ billion tests, according to the above criteria, only an infinitesimally small number of tests came out positive. Furthermore, as we can see from the Ordos data, the correlation of those ‘positive’ results with symptoms was extremely high. In other words, at least for those without previous recent infections, the percentage of false positives was very very low, thus making it into a very effective diagnostic tool. False negatives are another matter, however, as are positive results for the ‘recently infected’ category. Anecdotal evidence hints that even using a threshold of 35 for the latter group is probably too high to permit a meaningful interpretation.

Were the percentages of ostensibly false positive results using the same criteria outside of China higher? I.e. cases where, say, the cycle threshold X was exceeded but where the person lacked all symptoms? And if so, was this perhaps because many of those tested had some level of natural immunity due to prior infections? Or is the data simply not available? Is one reason why the data from China is so much less fuzzy because of the differentiation between those with natural immunity and those without it? Or are other factors at play?

These are just a few of the questions whose answers remain unclear.

Was Kary Mullis wrong?

One well-established narrative in Western resistance circles is the claim that PCR tests “don’t work” – i.e. that that cannot be effectively used to diagnose the presence of an infection. Those who endorse this view often cite a 1997 statement by American biochemist Kary Mullis to support this view. Mullis won the 1993 Nobel Prize in chemistry for his invention of the polymerase chain reaction, a technique used to amplify DNA.

So was Mullis wrong?

The short answer – no. To see why, let’s review what he actually said and see how it applies to what happened over the course of the past three years.

The quote in question stems from a July 1997 symposium in Santa Monica, California1. In the final minutes of the Q&A session, a member of the audience asked if PCR test results could be misused. To this, Mullis responded that the test cannot really be misused, but rather misinterpreted.

He continued: “… the PCR test is just a process that is used to make a lot of something out of something; it DOESN'T tell you that you are sick, it doesn't tell you that the thing you've ended up really was gonna hurt you.”

On the surface, both of the above statements are doubtless true. The PCR amplification process is a tool which produces numeric results. The interpretation of those results is another matter. For example, if you attempt to amplify any particular genetic snippet an endless number of times, you may eventually find it. But this does not necessarily make that finding meaningful. At the time, positive test results for HIV were often construed as being equivalent to an AIDS diagnosis, a claim for which there seems to have been extremely scanty evidence – if any at all. This misinterpretation however had nothing to do with the test itself.

25 years later, a lot of water has flowed down the Yangzi. While HIV has long since left the headlines and its purported link to AIDS has been widely discredited, many billions of sets of test data have been accumulated targeting a completely different set of genetic snippets. This test data was compared with actual illness in people and their ability to infect others. And it turns out that – unlike for HIV – some very reliable interpretations WERE found.

Transmission is a fact, regardless of whether or not viruses exist

Another popular narrative in Western alternative media is the claim that viruses “do not exist.” According to this line of argument, their existence remains unproven, and in particular, they fail to satisfy Koch’s postulates because none of these particles which are claimed to be ‘viruses’ have been proven to cause illness.

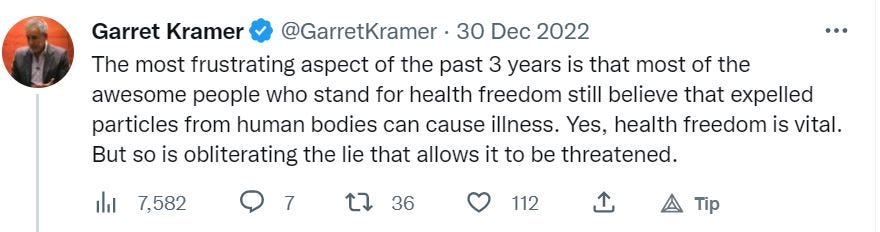

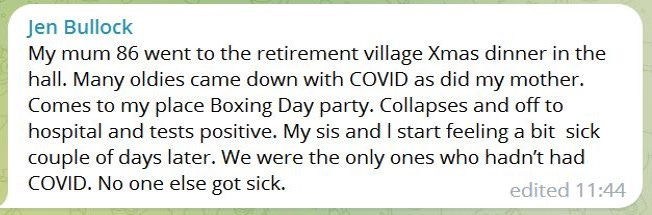

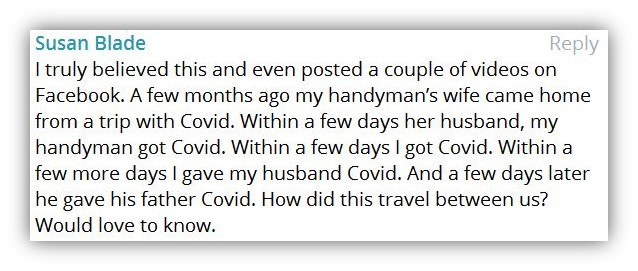

On this basis, it is frequently claimed that the idea of person to person ‘transmission’ or ‘infection’ is illusory. The illness called ‘Covid-19’ is not caused by a virus, but rather by toxins in the environment, 5G, or whatever. PCR tests are also therefore based on something non-existent. Here are two examples of this kind of position:

This point of view is particularly popular among strident supporters of Antoine Béchamp’s terrain theory.

Maybe this is true. Maybe it isn’t.

However, this is beside the point, because the question is irrelevant.

But but but …. if viruses don’t exist, how can claims about ‘transmission’ be true?

So goes the question.

The answer is that (1) collations of observed data (i.e. observations) and (2) attempts to explain these observations are completely different matters.

While confusion is perhaps understandable, it reflects a logical error.

For some reason many people espousing this perspective find it difficult to grasp that the reality of person-to-person transmission is in no way dependent on a particular explanation of HOW that transmission is taking place or what is being transmitted.

Thanks to Omicron’s extremely high level of infectiousness (R0 estimated in December 2022 at 22 or more) plus billions of test results, what we do know is:

Without a shred of a doubt, transmission of some illness-causing factor is taking place. This can happen by direct human to human contact but also within buildings, especially between households above or below each other. From what was observed in southern Chinese border cities, it is hard to avoid concluding that some kind of infectious genetic matter was literally blowing across borders.

This illness-causing factor is correlated with two specific genetic snippets which can be tested for.

This illness-causing factor is correlated with specific antigens which can be tested for.

And while the truth of the above three conclusions is overwhelmingly and unequivocally supported by the data from China, Chinese are hardly alone in finding such claims ludicrous. Here are a few examples of many of online comments along these lines:

In summary: The evidence is ample. Lessons abound for those with the interest to learn from them.

Follow us on Twitter @AustrianChina.

Mullis’ answer starts at minute 48:50 of Part 2 of the video recording.

Two other tentative lessons might be mentioned, but data are still lacking:

1) The vaccines deployed in China (Sinovac, Sinopharm) did not seem to protect Chinese from getting infected with Omicron; however, the government has published no comparative data. Nor is there any data examining whether or not the vaccines had any measurable effect on the severity of illness.

2) Three years of energetic containment measures apparently led to a highly susceptible population. The result was an Omicron tsunami which washed across China, infecting hundreds of millions of people at record speed and resulting in the death of large numbers of elderly. Would fewer people have died if Covid-19 had not been held at bay for so long? The answer is not clear, but it is without a doubt a key question.

Hi, thanks for your articles. I have a question about this statement:

"in Shanghai the cremation backlog is so severe that as a rule, multiple corpses are now being cremated together, thus commingling the ashes."

I've never seen any credible evidence from any country that health services, including crematoria, really were overwhelmed. It was clear to me that backlogs, bed shortages etc. were due to the treatment of Covid-19 differently to other infectious agents i.e. obsessive quaranting, cleaning, bureaucratically-imposed staff absences and PPE practices. Do you know if this could be a factor in Shanghai?

PS I note in one of your answers to another comment on this article that lockdowns may have caused a kind of backlog of elderly deaths brought on by respiratory illness. My understanding is that much of China was not in extended lockdown throughout the pandemic? I had the misfortune to live in one of the lockdown centres of the world, the state of Victoria in Australia. Before Covid really took hold here in early 2022, we experienced waves of other respiratory infections like the flu, other colds and RSV each time we came out of a 4 month lockdown.