View from China with an Austrian School of Economics Perspective

Today China’s National Health Commission declared that China had more new cases of Covid-19 than even before - 31,656 new COVID-19 cases, of which (so they say), 27,646 are “asymptomatic.” Unsurprisingly given the significant numbers of Shanghainese who have already been infected, this time around Shanghai’s numbers are among the lowest in the country. Guangdong and Chongqing are leading the pack this time, but with 1,656 cases Beijing is catching up. 加油!Go Beijing, you can do it!

Many (though not all) districts in Beijing are now effectively locked down, with Chaoyang being a notable exception.

Since we know that there is a huge incentive for authorities to under-report and for the infected not to test, we can be sure that the real numbers are significantly underestimated.

In addition, as we mentioned before during our coverage of the Shanghai lockdown, this term “asymptomatic” is rather misleading. It merely means that by the time these “new” cases were identified, they were not sick enough to need to be sent to a hospital. In our experience in Shanghai, most people who were deemed to have tested PCR-positive did indeed have at least some symptoms.

Meanwhile, struggles against nonsensical policies continue all over China. As we made clear previously in our article about the first few round of events at the huge Foxconn plant in Zhengzhou, these struggles are not only between the people and the government, but between multiple levels of government, as well.

Perhaps the most prominent of these struggles today is once again at the Foxconn plant. There factory workers have been battling both police and dabai (the folks in the white and blue outfits) in Zhengzhou. The primary reason for that struggle seems to be a failure of the part of Foxconn to make agreed upon payments for periods spent in quarantine, but the tension resulting from two months of Covid-related struggles is obviously a contributing factor. After factory workers sent the dabai packing the police were called in. According to the latest reports, the company has now issued an apology for the missing payments.

For Mandarin speakers, Wang Zhian just issued a report on this.

Another example is the recent struggle between migrant workers in Kangle (near Guangzhou) and the local government. We’ll get back to this story later, but in Kangle the upshot is also that the police and local government folded.

Shijiazhuang, a city 250 kilometers south of Beijing, is one example among many of the never-ending struggle between Beijing bureaucrats sitting in their ivory towers and local officials faced with real-life problems. On November 18th Shijiazhuang declared that they had given up on all testing requirements and were permitting all uninfected residents to resume normal life, only for the national government to step in several days later and reverse this decision, sending everyone back home again for 5 days of consecutive testing.

How many Beijing cases are required until the basement dwellers dreaming up unrealistic policies finally figure out that they are a failure? Some of us are waiting. Many others are taking matters into their own hands.

Wishful thinking in Beijing does not translate into reality

Time and time again China witnesses this never-ending struggle. Governments at various levels (national, provincial, city level, county level) attempt to institute an ill-considered top down framework. Governments at lower levels, and then ultimately the people themselves, nod their heads to say yes, yes, yes. But then within days or weeks workarounds are found, or – in many cases – the new policies simply get ignored.

上有政策,下有对策。Where higher authorities implement policies, the lower level authorities (or the people themselves) find counter-policies. So goes the saying. Sometimes these ill-advised policies end up getting formally repealed; sometimes they just dwindle away until replaced by something else.

This year we have seen countless examples of this.

One from June was the case from Tangshan where members of the local mafia beat up several women in a local restaurant. Tangshan is mid-sized city very close to Beijing. No-one died but several women were severely injured.

To put this into context, one must know that the current government declared the suppression of the mafia to be one of its great accomplishments (扫黑, 打击黑恶势力).

The Tangshan case illustrates the huge gap between such claims and reality. At first, the local police refused to arrest anyone. Only after a video of the assault went viral did the provincial government interfere and force the local police to take action. As soon as the public realized that the government planned to actually take action against the mafia, there were allegedly lines at the police headquarters to report other mafia crimes which the police had previously refused to deal with. In the end, 28 people in total from the local mafia were arrested and sent to Langfang for trial. (Apparently there was significant doubt that a fair verdict would be forthcoming in Tangshan.) Three months later all were sentenced, with the ringleader getting a sentence of 24 years.

Not only was the local mafia apparently above the law, but this was the status quo in a city only 150 kilometers from Beijing.

The reality is that in contrast to wishful thinking in Beijing, the mafia all across China is stronger than ever, and in almost all cases works closely together with the police. In many cases, these groups are in fact run by ex-police officials. Apparently the Tangshan mafia earned its keep primarily by demanding protection money (保护费) from local shops and street-sellers, as well as by acting as a debt collection agency (讨债). While this doesn’t mean that these local mafias have unlimited license to act as they please, it does illustrate the national government’s rather weak ability to roll out its policies.

Here’s how that is playing out on the Covid front:

On the one hand, Beijing government officials continue to swear China will stay the course. Rumors have it that additional hospitals and fangcang are in the works.

Yet at the same time, on November 11th a huge set of new ‘relaxed rules’ was announced. The purported goal of these relaxations was to both reduce the number of restrictions on domestic and international travel, as well as to unify the vast sea of differing rules and regulations in effect in the cities, provinces and even districts across China. For example, the quarantine period for incoming travels from abroad was rolled back to 5+3 days. The silly so-called circuit breaker rule was also abolished, whereby airlines would be punished with flight cancellations in case any of their passengers later tested positive. The tracking of secondary contacts (contacts of contacts) was terminated. And people arriving from so-called high-risk areas are no longer to be sent to centralized quarantine facilities; instead, home quarantine is to be the rule.

The policy writers correctly realized that this chaos was severely impacting the economy and decided to do something about it. Nice idea, but 2 weeks later this ‘unification’ of policies seems to be seriously fraying. Shanghai just announced a new set of restrictions for incoming travelers from other provinces (starting on November 24th, no visits to so-called public venues like supermarkets for 5 days), and even each district in Beijing has its own set of rules. Shanghai is now allegedly planning to team up with neighboring provinces to create a special travel bubble allowing residents to visit public venues in each other’s provinces without required a 5-day wait first.

Chinese officials have one again proven Mises’ adage that interventionism only leads to more interventions to fix the problems caused by the previous ones.

In some cases, this never-ending quixotic struggle on the part of the national government to implement its policies nationwide may seem like a failure. We should however not forget that it is also one of the key factors limiting the amount of damage which demented centralized policies can inflict. It’s why in reality few restaurants in China demand that diners scan their “site” QR codes, and why lockdowns get repeatedly ignored.

At the same time, not only is the national government weak, but in many ways the local governments are, as well. For one thing, they are constantly at risk of losing face when local scandals manage to get national attention. When videos of angry residents hit the social networks, this makes local authorities look bad and tends to force these authorities to compromise. Censors attempting to keep a lid on discontent keep churning their hamster wheels, yet to little avail. Second, they are dependent on a flow of local tax receipts for their income. If the economy fares poorly, the local officials get black marks on the HR record. These two factors put a limit on their ability to enforce both bad and unpopular policies. Of course this doesn’t stop them from trying; it just means that there is a balance. Push things too far and there is risk of pushback. In economically important areas this balance works fairly well. Where it works less well is in economically backward rural areas such as Feng County near Xuzhou, where local officials successfully covered up a wife-trafficking scheme for decades.

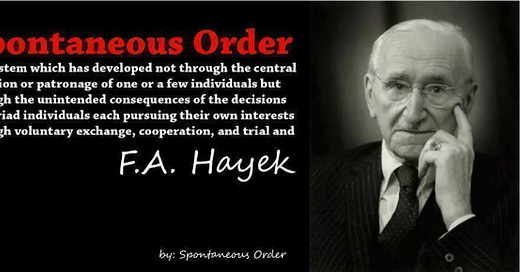

The recent Kangle (广州海珠区康乐) case mentioned earlier is a good example of this. There was a Covid-19 breakout there which led the local government to impose a lockdown. Kangle is a center for textile production and much of the work is carried out by migrant workers from Hubei province. Both production and sales are organized bottom up by the marketplace (what Hayek called ‘spontaneous order’) with few large companies and many small to medium sized family businesses. Few of these workers are formally registered there, so the local government has only a somewhat vague idea of who lives there and what is going on. This scenario offers ideal conditions to illustrate the futility of attempting to run a command economy.

When the lockdown was declared, the government said it would supply food to the residents, but did not bother to consider the bulk of the actual population, namely the unregistered residents. Unfortunately, it must be said that such incompetence is typical. Food deliveries went only to the local Cantonese (the ones primarily living off of rent payments) and not to the people doing the actual work. Moreover, the local dabai attempted to monopolize food sales, reselling food at high prices. Finally, the government imposed lockdown prevented production during the run-up to the 11-11 e-commerce bonanza, the Chinese equivalent of the American Black Friday. This meant a huge loss of income.

Workers were angry and there were riots, pictures of which were widely shared. The upshot: Local authorities caved across the line and gave the migrant workers what their representatives asked for.

The struggle continues.

Update today from the Foxconn front: Foxconn is offering workers 10,000 yuan to leave.

https://www.zerohedge.com/markets/foxconn-offers-workers-1400-leave-china-iphone-city-after-mass-chaos

Meanwhile, street battles in Kangle seem to have resumed:

https://twitter.com/AnonymeCitoyen/status/1596027612018638848

You write as if the Chinese government believes in its own propaganda. That cannot be so, because they created the propaganda in the first place.

In other words, when the government locks down Shanghai, it's not the public health they have in mind.