When the Commissar Came to Shanghai

Vice-Premier Sun Chunlan doubles down on Beijing's Zero Covid policy and imposes her style of enlightened central planning on Shanghai.

View from China with an Austrian School of Economics Perspective

Ms. Commissar (Vice-Premier) Sun Chunlan is now in Shanghai, one of the world’s most populous and prosperous cities, to make sure that its 26 million people are being given the right marching orders to deal with its ongoing Omicron outbreak. Which means doing things the Beijing way. Which means the Xi’an way, since their lockdown was so successful. And the Jilin way – the other major Chinese city currently being put through the zero-Covid wringer.

As mentioned in our 2021 year end piece entitled Cross-Examining China’s 2021 Cancel Culture, Chinese provinces have wildly differing governing styles and even in today’s increasingly less free times, still retain substantial autonomy in interpreting and carrying out national government policies. Of all Chinese provinces, Shanghai’s version of the night watchman philosophy has been consistently among the most liberal in China, in the classic sense of that word.

This was also true during the Covid-era — until Commissar Sun’s arrival.

Over the past few weeks there were actually a number of signs that the sands might be shifting in Beijing and that plans might be afoot to come up with a policy more realistic than the “zero-Covid” approach propagated by the government since mid 2020. As usual, Shanghai seemed to be leading the way towards finding a new equilibrium. The media propaganda shifted somewhat from broadcasting fear of the virus towards the idea that maybe it wasn’t so bad after all and that ample treatment was available. Encouraging hints.

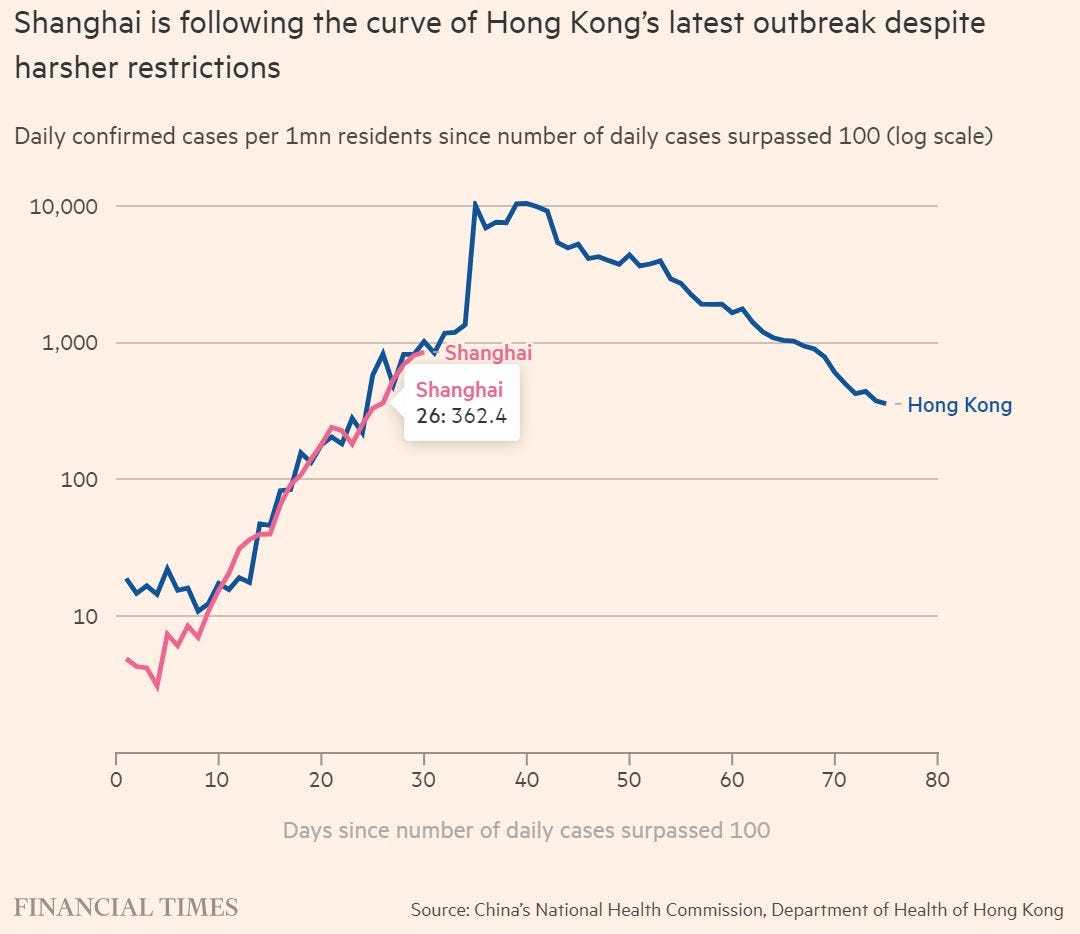

Even in China it has become increasingly obvious to those inclined to independent thought that the latest version of the “virus” (Omicron or whatever Greek letter you want to award it), is not compatible with China’s official '“Zero Covid” policy. It is simply too contagious to stop for long and is thus all but impossible to contain. With a drastic lockdown maybe you can slow down its spread, but not for long. Moreover, given that it rarely impacts the lungs and is not very dangerous, it’s hard to avoid asking the obvious question: How can one possibly justify shutting down society to combat what is clearly nothing more than a severe flu?

For a few weeks, rationality seemed to be making a comeback. But then someone in Beijing said no.

As one Shanghai insider put it:

“After Sun (Chunlan) took over the epidemic prevention work in Shanghai, the original epidemic prevention command system was completely taken out of the loop. Shanghai’s leaders and experts basically all went collectively silent, with the sole exception of the local Communist Party Secretary Li Qiang openly supporting Vice-Premier Sun.

Shanghai's original plan was to isolate asymptomatic infected people at home, using the local neighborhood committees to supervise and support these cases, while sending the more serious cases to hospitals. Compounds and buildings should be shut down as little as possible, and effects on economic life and people's lives should be minimized. This plan was widely agreed upon by the leadership and experts in Shanghai, and the outbreak of Omicron in Shanghai for nearly a month without a single case of serious illness or a single death had already generated substantial confidence in the validity of this approach within the Shanghai people. Shanghai wanted to deal with this wave of Omicron strain without closing the city and affecting the economic operation and the life of the citizens.

When news of this plan reached Beijing, it was severely criticized by the national prevention and control command team. In response, they ordered Shanghai to announce a two stage city lockdown. Commissar Sun went to Shanghai to take command, after which she arranged to bring in national government medical and military forces. All of this in an effort to create a “showdown” against Shanghai's attempt to move toward coexistence with the virus.” [from a non-public Chinese language source]

Instead of “moving towards coexistence with the virus,” what happened is this:

On the evening of March 27th, Sunday evening, at 8:23pm the Shanghai government issued a notification of a general lockdown across the city starting Monday, initially for four days. Pudong on the east side of the city was to be the first victim, then Puxi on the west side several days later. Those initial 4 days eventually turned into 14 days and counting.

Given the notorious unreliability of announced lockdown timelines, in Pudong there was a massive panic to purchase supplies in the remaining 1 ½ hours before the last shops shut down. All remaining open stores were packed, providing perfect conditions to spread Omicron quickly and broadly. Which it did.

Then everything was blocked off, including most delivery services, and each household was left to fend for itself. Those with insufficient stocks of food, or who had the habit of frequently ordering takeaway, ended up being pretty hungry.

A few days later, the Commissar did however start to provide deliveries of essential supplies:

No doubt a good deal for the Spam producer who got more business through that one government connection than he would be able to sell in a month otherwise. And as an added benefit, a lot of people who don’t eat fake meat now have a can of it decorating their tables.

It is a fine example of the merits of central planning.

Meanwhile, while the planners were choosing their Oreo and Spam suppliers, many people were running short of real food. Thanks to the non-existent advance warning, some in fact had none at all, because they were locked down at their place of work and could not return home. This applied to many of the maintenance staff in one Shanghai compound we know of. No food, no cooking facilities, no pillows, no blankets.

Many such issues were quickly discovered on Day 1, which was actually a beautiful day during which many rounds of tennis and badminton were played. Some solutions to the above mentioned issues were found by ordinary people, as is their wont – solving problems. Supplies and materials were found and donated.

Apparently word reached the Commissar that many people were having fun, so on the morning of Day 2, she banned fun. Henceforth no-one was to set foot outside his or her door unless to go for Covid testing or on official business. Many people decided that could not possibly include a prohibition on walking the dog, so dogs did a lot of that. And quite a few housing compounds were less than industrious in enforcing what most people considered to be nonsensical policies. Nonetheless, no doubt quite a few dogs remain stuck inside in apartments all around Shanghai.

All of these ground level instructions come from so-called neighborhood committees – the 居委会 (jūwěihuì). These are a relic of socialist times, when they were responsible for keeping an eye on and ratting on dissidents. In today’s modern China, normally one hardly even notices they exist. Now they’re back.

As days passed, some people got sick. Some, because people just get sick. It happens all the time, especially if you’re sitting around locked up in a small dark space the entire day. If you are able to deal with it yourself, fine. But what if not? It’s not so easy to get help when everything is blocked and only limited transport is available. In one publicized incident just before the general lockdowns started, a nurse suffering from allergic shock was rejected by her own hospital. She died before she could reach a different one. Who knows how many others have died or suffered unnecessarily due to a lack of care? Doubtless tens of thousands at a minimum. In theory the neighborhood committee people are supposed to help deal with such issues, but there are 26 million Shanghainese, versus how many neighborhood committee staff? And they also have their own struggles to deal with.

Others got sick from – imagine that – Omicron. After a week’s delay, Commissar Sun sent over some boxes of Chinese medicine (Lianhua Qingwen pictured above) for dealing with Omicron, and while these may be helpful, they came a few days too late for most people to make use of. One hard-to-forget video doing the rounds on social media shows an exasperated mother facing deportation whose 4-month old son struggled through a 40-degree Celsius fever while his mother and several other family members were all feverish with Covid/Omicron. Most were simply left at home to cope as best possible. Imagine that, a disease so terrible that it’s worth shutting down society over, but for which absolutely no treatment is offered or provided. No pills, no instructions, nothing. Not even a sheet of paper with pretty pictures on it. (HCQ and ivermectin remain both cheap and readily available in China but practically no-one is aware of their effectiveness against Covid.)

I guess this detail just slipped the Commissar’s mind. Can’t think of everything, right? Before Commissar Sun’s plan was set in motion, a few unlucky souls who were picked up and identified as being ‘sick’ were actually brought to hospital isolation wards. From what we have heard, bad food and no treatment at all was the norm, but at least in theory they were in actual hospitals where in case of emergency some actual help might be obtained.

During the lockdowns, sick or not, pretty much every other morning every household in each housing complex or compound is told to forget the ban on leaving their apartments. Instead, they are told to line up somewhere outside and provide yet another round of samples for PCR tests. Social distancing has never been seriously implemented in China’s densely inhabited cities, and at least in many compounds the first round of testing was likely yet another super spreader event.

By the time everyone started lining up for the second round of testing, it seems that someone with authority realized what had happened and attempted to insist on keeping distance between those in line. Though not of course between the person being tested and girl in the white space suit costume taking the sample. Some of the costumed people are now also starting to test positive.

Love it or hate it, it’s hard to deny that practice does make perfect, and mass testing has been developed into a highly calibrated science, complete with the accompanying super spreader opportunities. Everyone is told to register via cell phone mini-app and generate a QR code to be scanned before submitting the sample. Doesn’t always work perfectly, particularly for foreigners, but a QR code is usually to be had in the end. 10 samples are combined in one test bottle to save time and money. If there is an issue, secondary individual tests are the following day. About 12 hours later – or many more if you’re unlucky – you should be able to review the result in your health code mini-app. On the odd days the neighborhood committee staff pass out quick antibody tests. Everyone is expected to do them and upload pictures of the results to a local Wechat group.

PCR test samples are tested for two different genetic snippets – one called ORF1 a/b and the other the N-gene. Results are scored based on the number of CT cycles required to get a positive result. For those not yet on the Covid hot list, these days only results over 40 are considered to be negative, although bizarrely once one is ON the hot list, test results over 35 for both snippets are sufficient to put one on the path towards eventual release from Covid detention.

If you want to avoid the camps, you need two sets of test results over 35 during the last week before the end of the lockdown. But – and here’s the catch – as soon as you fail once, you are ‘confined to quarters’ and typically no longer eligible for any more tests. Until you get to the camp. So even if you recover quickly and are in reality back over 35, you probably won’t be able to prove it before you end up in the camps.

Once you’re in the camps, getting out is even harder. There you have to test four times consecutively over 35 on both scales. There must be a gap of at least 24 hours between each test. Apparently thus far few if any of the internees have succeeded at meeting these criteria and actually getting out.

The COVID Camps – 方舱医院 / 隔离点

Now we’re getting to the real nitty-gritty: the whole point of the exercise – namely, to corral the infected and suspected, and then deport them to the camps, thus “protecting” society from the virus. Or so the Commissar tells us. When we write ‘camps’ in English, we are usually referring to mass facilities which are rather euphemistically called ‘方舱医院’ (fāngcāng yīyuàn - square cabin hospitals) in Chinese Newspeak. These are the facilities targeting people who have tested positive. They have existed in theory since Wuhan times, but as discussed in our previous background piece on China’s Covid regime, in reality they were rarely used. Instead, truly sick people were sent to the hospital, while others subject to quarantine got sent to hotels.

Besides these ‘fāngcāng yīyuàn’, there are also other facilities called more simply ‘gélídiǎn’ (隔离点) or isolation or quarantine centers. These are for people identified as close contacts of positive tested people (密接). They have a different name and are segregated from the previous category, but the facilities seem to be similar. They are however in some respects even worse, because unlike the fāngcāng yīyuàn, which mostly contain people who are either truly asymptomatic or who were scooped up after already having mostly recovered from Covid, the so-called isolation centers are full of people whose disease cycle is just ramping up. Moreover, from what we have heard, they offer neither medical care nor even any medicine. Not even ibuprofen or cough syrup, unless someone was prudent enough to bring a supply with them. After all, according to their paperwork, they are healthy - and healthy people don’t need medicine.

There also seems to be thus far no criteria for obtaining release from this particular type of camp.

The word ‘concentration camp’ for all these facilities would seem more appropriate, since they may be a number of things, but one thing they are certainly not is a hospital. Nor do they serve to isolate their residents from anything since they are packed together with thousands of others, many of whom are sick.

In the old days the word used to describe deporting someone to a camp would have probably been ‘遣送’ (‘qiǎnsòng’). The Newspeak word for this is ‘转运’ or ‘zhuǎnyùn’, meaning something like ‘to transport on to the next stop’). During Week 1 the plan was allegedly to use ambulances to haul off everyone who tested positive and/or were identified . That’s how things started, but the numbers quickly grew to point where cases vastly outnumbered ambulances. Whereas numbers at the outset were around 3500 people per day, now we’re over 20,000 per day not including the close contacts. That’s not going to work with ambulances. So we’re back to buses.

Moreover, if all these people are to be forcibly taken from their homes, they will need to be taken somewhere and fed, supervised and provided with medical care (in theory!). Facilities for such massive numbers of people simply do not exist, and aren’t easy to create on the fly, either, especially if you’ve just shut down the civilian economy. Nonetheless, the Chinese government is good at squeezing water out of a stone, so something makeshift does get built. Given the circumstances the facilities actually seem for the most part to be passable, if only from a technical perspective. Just no medical care. They do all seem to offer reasonably reliable Internet access. Just don’t forget your charger!! There are a number of videos on the Internet showing the conditions, e.g. this one from the repurposed Shanghai Exposition Center:

We are told that most of these cases are asymptomatic, but in reality it’s impossible to know the real numbers, since a lack of symptoms is defined in terms of the symptoms common for cases of the old virus which existed back in 2020 – i.e. lung inflammation visible using a CT scan.

Maybe this was cutting edge for 2020, but the 2022 virus has mutated and now provokes a different set of symptoms. This leaves 2020 definitions meaningless.

In reality probably quite a few people have symptoms, the most common being 2-3 days with a nasty sore throat, watery mucus and 39C fever, then several more days with coughing. With effective treatment such as HCQ a bit shorter, without treatment a bit longer. Rarely life threatening but certainly unpleasant. In any case, these unpleasantries apparently evoke little interest at the Commissar’s office, since the plan seems to be to let most of the infected deal with the symptoms on their own. What interests the Commissar is maximizing camp admissions. This may sound like a cynical take, but that is literally the crux of the dispute between the Commissar and the Shanghai government. Remember, the Shanghai government plan called for no camps at all. If there is a medical logic for packing large numbers of infected people in small spaces, it has not been well publicized.

At this point, the number of households ‘eligible’ for deportation far exceeds the capacity of the government to transport or house them, but the Commissar nonetheless set a goal for the remaining scheduled deportations to all take place before April 11th. Needless to say, enthusiasm for going to the camps is non-existent. Few see any point in them other than satisfying a government power trip, though as in the West there is always a minority which supports all government acts of coercion or force, as long as they are carried out in the name of “keeping us safe.”

Anger, frustration and fear are omnipresent.

To date, as of April 8th, 2022, the Commissar is sticking to her guns and has granted a very short (though slowly expanding) list of exceptions, namely:

Households which include foreigners

Households which include children under 2

Households which include elderly over 80

Households with a special medical situation, such as people convalescing after major surgery

Those eligible for an exception are permitted to quarantine at home until they can pass the tests and sit off the required number of additional quarantine days.

The exception for foreigners was obtained after the French General Consulate sent a formal complaint to the Shanghai government on behalf of the EU with 6 demands regarding the treatment of EU citizens living in Shanghai. In particular, they raised two clever demands: for one thing, they reasonably demanded that interned foreigners be guaranteed access to English-speaking medical help. Since the Shanghai authorities in reality aren’t even able to guarantee access to Chinese-speaking help, that already was a killer criterion. Second, they demanded that authorities arrange for personnel to feed pets forced to stay at home without their interned owners. Eminently reasonable. What are the pets supposed to do? Starve?

Of course, the reality is that the understaffed government which is trying to feed a city of 26 million people and to replace the miracle of spontaneous decentralized order with a command economy, is completely overwhelmed with far more mundane tasks, much less feeding pets.

The result? Foreigners are now exempted. For the moment.

Same result for their literally inhumane initial policy of separating mothers from their children. Axed. For the moment.

These “policies” can and do change every day.

All of these experiences have been extremely shocking for most Shanghainese. As discussed in our previous article on everyday life in China, contrary to the cartoonish version of China which is often on offer in Western social media, in everyday life most Chinese have very little interaction with the state, leaving many with assumptions left over from their schooling about it being a benevolent figure. Now a lot of them have been forced to realize that it is anything but benevolent, especially the one in Beijing imposing its will on Shanghai.

When the material and human resources in the economy are allocated through the interaction of millions of independent decision makers, spontaneous order emerges and in the process an endlessly long list of needs are met and desires satisfied. When by contrast the state’s central planners are ‘running’ things, many of their acts and decisions come across as cruel, callousness, nonsensical and arbitrary. People under 40 have never before in their lifetimes experienced such an environment. It is a heady experience, and all in all, perhaps one with some good lessons on offer about the reality of the world in which we live.

As is the case in many places all across the world, the struggle between a tiny number of totalitarians and the rest of humanity continues. The notion that a highly efficient economy as complex and multifaceted as the Chinese one could even by partially ‘run’ by central fiat is even in theory nonsensical. Now millions are seeing the reality of this truth played out before their eyes.

For the moment, the Shanghai government remains sidelined and its officials remain for the most part completely unconvinced of the merits of the policies they are being asked to enforce. Many millions of people in both Shanghai and Jilin, including many in government positions, are fed up and angry.

Not all of these people are influential, but many do manage to get their voices heard, and many were highly influential to start with. Their voices are having an effect and will continue to do so. Regardless of where this leads short-term, these events will not be easily forgotten.

As Ayn Rand once put it, you can choose to ignore reality, but you can’t choose to ignore the consequences of reality.

A situation update for April 10th is available here.

Great article Austrian China.

Thanks for posting quality info.

Love your substack.

All the best

First rate. A level of detail not available in western reporting certainly. Perhaps unfortunately, this will feed the cartoonish image of China bad in the western press, and social media.

October will be interesting: